The World Health Organization (WHO) states that palliative care is an integrated and patient-centered approach that helps reduce the suffering of any advanced cancer or chronically ill patient and their family.[1,2] The World Health Assembly passed a resolution on palliative care in 2014, which includes palliative care in the undefined sustainable development goal-3, and now, the WHO has elevated and optimistically positioned palliative care from a peripheral to a central aspect of healthcare.[3,4] By 2060, the global burden of palliative care will rise to 48 million people per year. Among these, 83% of deaths due to cancer will happen in low- and middle-income countries, including India.[5,6]

According to the GLOBOCAN-2020 study, there will be 1,00,000 new gallbladder cancer (GBC) cases and 8,000 GBC deaths worldwide in 2020.[7,8] In that year, GBC had 0.6% (ranked 25th) of new cases, and global mortality rates were 0.9% globally in 2020.[9-11] While developing palliative care bundles, the Principles of the International Association for Hospice and Palliative Care[12,13] for palliative care were followed. Palliative care does not have this well-defined care bundle to provide comprehensive care to advanced cancer patients and their families.[14] As a result, an innovative, cost-effective, and safe palliative care bundle is required to improve functional recovery, resilience and quality of life for advanced cancer patients and their families. This study aimed to develop, validate and test a standardised palliative care bundle on functional recovery, resilience, and quality of life among advanced GBC patients and their caregivers.

MATERIAL AND METHODSA single-centre and two-arm randomised controlled trial (RCT) was employed to test the effectiveness of the palliative care bundle on 116 participants (58 in each arm) of All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), Rishikesh, India, in which patients diagnosed with advanced GBC enrolled and follow-ups were done till 4th months of their palliative treatment. The research was conducted in the Surgery Outpatient Department (OPD) at AIIMS, Rishikesh, from July 2019 to December 2021. The sample size calculation formula used was as follows: n=2a+b2$μ1−μ22 where a = conventional multiplier of alpha, where alpha is 0.05; b = conventional multiplier of beta, where beta is 0.80; $ = population standard deviation (SD) difference; µ1 = population mean in treatment group 1; µ2 = population mean in treatment group 2 and n = sample size in each group. The intervention group (IG) mean ± SD was 36.1 ± 13.5, and the control group (CG) mean ± SD was 45.1 ± 16.5, used for sample size calculation.[15] Using a statistically superior methodology for RCT, a sample size of 48 participants per trial arm (n = 96) was computed. With a 20% loss to follow-up rate and a correction factor of ([96/96–20×n], n = 58), 58 participants were expected to be enrolled in each group.

RandomisationRandomisation was done by simple random sampling technique with the use of computer-generated block randomisation list. Independent person generated a computer-generated block randomisation list (four blocks) for 116 participants (Seed No: 260737520056968).

AllocationAn open list of random number tables used for implementing random allocation sequences by 1:1 ratio into both intervention and CG. Using a computer-generated random number table, patients were randomly assigned to IG and CG in a ratio of 1:1.

BlindingBlinding of a physician for palliative treatment and statistician after assignment to the palliative care bundle. Patients who age more than 18 years, have access to a smartphone, are able to understand English or Hindi language, are diagnosed with GBC[16,17] of stages III and IV, are on palliative treatment (4–6 cycles of Gem + Cis),[2,18] Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) score from 0 to 3[19] and having at least one caregiver of age more than 18 years who is physical and mentally fit were included in the trial. Patients who were unwilling to participate were excluded from the study.

Development of palliative care bundleDevelopment and validation of the palliative care bundle include five phases. Phase I includes item development, in which, by searching PubMed and EMBASE databases, ten items were identified for the palliative care bundle. The face validity of those items was done by 11 experts, which included four palliative care physicians, three palliative care nurses, two social workers, and two advanced GBC patients. Content validity was assessed by quantitative assessment, including content validity index, content validity ratio, and kappa values.

Phase II includes testing validity and reliability of the palliative care bundle by construct validity by exploratory factor analysis by Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin test. Reliability was calculated for the internal consistency of each item by Cronbach’s α coefficient.

Phase III includes training of health professionals done after selecting two pilot wards by consulting with the senior nursing officers to discuss the proposal, the intervention, and desired outcomes.

Phase IV includes the implementation of a palliative care bundle after proper training. The palliative care bundle was tested and implemented on 25 GBC patients for 15 days, and their data were collected. We also collected in-depth knowledge regarding the feasibility of how to administer the palliative care bundle and collect data within a specific time period. The data were then sent to the organisation’s strategic planning committee on a monthly basis for monitoring.

Phase-V includes evaluation which was done by standardised scale that is, functional independence measure (FIM) scale,[20] brief resilience scale (BRS),[21] EORTC QLQ BIL-21,[22,23] Zarit burden independence (ZBI) scale,[24] modified integrated palliative care outcome scale (iPOS)[25] and ECOG[26] and pain for evaluation of palliative care bundle effectiveness.

Testing of the palliative care bundleWe selected two pilot wards, that is, the radiation oncology and surgery ward, in which 25 GBC patients and their caregivers were selected, and a palliative care bundle was implemented on each patient for 15 days after recruitment.

Palliative care bundleEach IG patient received problem-solving counselling and symptom management information, bhastrika pranayama training, and each caregiver received percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) tube care training, symptom management information, and Sudarshan kriya training. They practice all palliative care bundles for four months. A booklet was provided to each patient and caregiver, which included all information related to the palliative care bundle. Regular telephonic follow-ups, reinforcement, OPD follow-ups, problem-solving counselling, random return demonstrations, and re-demonstrations were done. A daily palliative care bundle chart was maintained by each patient and caregiver at home.

Primary and secondary endpointThe primary objectives of this study were functional independence, resilience, quality of life, and caregiver burden after four months of palliative care bundle intervention. The secondary objectives were palliative care outcome, ECOG, and pain after four months of palliative care bundle intervention.

Data analysis was done by calculating frequency, percentage, mean, SD and paired t-test using SPSS version 23.0. Analyses were conducted using the intent-to-treat principle and last reading carry forward technique was used for dropout and lost to follow-up cases.

Ethical approval was obtained by the Institutional Ethical Committee (AIIMS/IEC/19/912) of AIIMS, Rishikesh. The study was registered under the Clinical Trial Registry of India (CTRI) (CTRI/2021/01/030791). Written informed consent was obtained from each study participant, and their confidentiality and anonymity were maintained throughout the study.

RESULTSA total of 150 participants were evaluated, and 116 participants who met the eligibility criteria were enrolled in the study. One hundred and sixteen participants were randomly assigned among IG or the CG, with 58 numbers in each group. The overall recruitment rate was 96.7%, and the retention rate in the trial was 86.2%. By the end of 4th month, the acceptance rate was 93% and adherence rate was 85% [Figure 1].

Export to PPT

Patient’s baseline profileThe average age of participants was 52.18 ± 1.23 years, female (65%), married (95%), Hindu religion (82%), literate (100%), and doing low-wage work (65%). Around 46% of the participants had an income of 10,001–20,000 INR/ month. About 41% of participants belong to rural areas, and the majority of caregivers were their spouses (75%). Both groups, that is, control and IG, were statistically homogenous (P > 0.05) except in terms of the age of patients because most of the participants in IG belong to the more than 60 years age group, whereas in CG, the majority belongs to 50–59 years age group [Table 1].

Table 1: Baseline profile of patients (n=116; n1=58 and n2=58).

Variables Options Intervention group (n=58) f (%) Control group (n=58) f (%) Total (n=116) f (%) P-value Age (years) Mean±SD 50.34±1.45 54.03±1.01 52.18±1.23 0.0001@* 20–39 years 14 (24) 02 (04) 16 (28) 0.010$* 40–49 years 12 (20) 18 (30) 30 (26) 50–59 years 14 (24) 20 (34) 34 (29) More than 60 years 18 (32) 18 (32) 36 (31) Sex Male 21 (36) 20 (35) 41 (35) 0.845# Female 37 (64) 38 (65) 75 (65) Marital status Married 57 (98) 53 (91) 110 (95) 0.206$ Single 01 (02) 05 (08) 06 (05) Religion Hindu 46 (79) 49 (84) 95 (82) 0.469# Others 12 (21) 09 (16) 21 (18) Education Primary 07 (12) 09 (15) 16 (14) 0.778# Middle 08 (14) 12 (21) 20 (17) High school 14 (24) 11 (19) 25 (23) Sr. Secondary 07 (12) 05 (09) 12 (10) Graduate and above 22 (38) 21 (36) 43 (36) Occupation Home makers 06 (10) 09 (15) 15 (13) 0.681# Low wages worker 38 (66) 37 (64) 75 (65) Medium and High wages worker 14 (24) 12 (21) 16 (45) Income (INR) per month Less than 10,000 10 (17) 10 (17) 20 (17) 0.827# 10,001–20,000 25 (43) 28 (50) 53 (46) More than 20,000 23 (40) 20 (33) 43 (37) Residence Rural 21 (36) 27 (47) 48 (41) 0.438# Urban 14 (24) 14 (24) 28 (24) Semi-urban 23 (40) 17 (29) 40 (35) Caregiver’s relation Spouse 47 (81) 40 (69) 87 (75) 0.133# Primary relative 11 (19) 18 (31) 29 (25) Personal habits and clinical profileMajority of participants were non-vegetarian (78%), non-smokers (78%), non-alcoholic (75%), and using groundwater (57%) for drinking. In the study participant’s personal habits, no statistically significant differences were found between intervention and CG. The clinical profile of study participants depicted in [Table 2] showed that 62% of participants were diagnosed with Stage-III GBC. Nearly, 64% and 77% of GBC patients had positive symptoms of fever and jaundice, respectively. Overall study participants ECOG depicted that 72% of participants reported an ECOG score of 2. There was no significant difference between intervention and CGs at baseline, so both groups were comparable in terms of their clinical profile [Table 3].

Table 2: Personal habits and clinical profile of participants (n=116; n1=58 and n2=58).

Variables Options Intervention group (n=58) f (%) Control group (n=58) f (%) Total (n=116) f (%) P-value Diet Vegetarian 10 (17) 15 (26) 25 (22) 0.228 Non-vegetarian 48 (83) 43 (74) 91 (78) Smoking Yes 13 (23) 12 (21) 25 (22) 0.084 No 45 (77) 46 (79) 91 (78) Consuming alcohol Yes 15 (26) 14 (24) 29 (25) 0.096 No 43 (74) 44 (76) 87 (75) Drinking water supply source MCD 13 (22) 19 (33) 32 (28) 0.564 Ground 36 (62) 30 (52) 66 (57) Natural water source 09 (16) 09 (15) 18 (15) Stage Stage 3 36 (62) 37 (64) 73 (62) 0.062 Stage 4 22 (38) 21 (36) 43 (38) Fever No 21 (36) 21 (36) 42 (36) 0.072 Yes 37 (64) 37 (64) 74 (64) Jaundice No 13 (22) 14 (24) 27 (23) 0.092 Yes 45 (78) 44 (76) 89 (77) ECOG 2 44 (76) 39 (68) 83 (72) 0.486 3 14 (24) 19 (32) 33 (28)Table 3: Mean, SD and independent ‘t’ test values.

Scale FIM scores Intervention group (n=58) (Mean±SD) Control group (n=58) (Mean±SD) tvalue (P-value) 95% CI (Lower; Upper) FIM scale Baseline 111.02±11.78 93.60±5.91 10.07 (0.0001*) (13.99; 20.84) 5th follow-up 86.77±6.96 78.15±9.86 −5.43 (0.0001*) (−11.76; −5.47) BRS score Baseline 2.09±0.43 2.17±0.37 1.01 (0.313) (−0.07; −0.22) 5th follow-up 4.03±0.84 2.61±0.41 −11.39 (0.00011*) (−1.66; −1.17) EORTC QLQ BIL-51 Scale Baseline 160.31±12.81 162.86±13.06 1.06 (0.291) (−2.20; 7.31) 5th follow-up 111.02±21.24 148.45±14.95 10.97 (0.000*) (30.67; 44.18) ZBI scale Baseline 68.12 71.88 1.09 0.313 5th follow-up 33.15 83.85 −8.12 0.000* Modified iPOS scale Baseline 36.13±2.48 36.44±2.93 0.614 (0.540) (−0.69; 1.31) 5th follow-up 25.98±4.07 33.25±2.46 0.013 (0.0001*) (6.03; 8.51) Comparison of FIM, BRS, EORTC QOL BIL-51, ZBI scale and Modified iPOS scale scores of IG and CGFIM score data were normally distributed (Kolmogorov– Smirnov Z testing, z = 0.928 and P = 0.355), BRS scores data were normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z testing, z = 0.650 and P = 0.792), EORTC QLQ BIL-51 score was normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z testing, z = 0.836 and P = 0.487) and Modified iPOS scores were normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z testing, z = 0.743 and P = 0.639); hence, independent ‘t’ test used whereas ZBI scores was not normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z testing, z = 1.950 and P = 0.001); hence, Mann–Whitney U-test used for analysis.

Baseline mean FIM score was 111.02 ± 11.78 in IG, whereas CG had 93.60 ± 5.91 with a 95% confidence interval (CI) (13.99–20.84, P = 0.0001*), hence the difference in baseline FIM scores of both groups due to the difference in the geographical region of Uttarakhand. At the 5th follow-up after four months, the mean FIM score was 78.15 ± 9.86 in CG, whereas IG had 86.77 ± 6.96 with 95% CI (−11.76–−5.47, P = 0.000*); hence, significant values indicate the effectiveness of palliative care bundle in terms of more functional independence of patients in IG over CG.

The baseline mean BRS score was 2.09 ± 0.43 in IG, and CG had 2.17 ± 0.37 with 95% CI (−0.07–0.22, P = 0.313), and hence, both groups were homogeneous in baseline BRS scores. At the 5th follow-up after four months, the mean BRS score was 2.61 ± 0.41 in CG, whereas IG had 4.03 ± 0.84 with 95% CI (−1.66–1.17, P = 0.000*), where significant values indicate the effectiveness of palliative care bundle in terms of better resilience of advanced GBC patients in IG over CG. The baseline mean EORTC QLQ score was 160.31 ± 12.81 in IG whereas CG had 162.86 ± 13.06 with 95% CI (−2.20–7.31, P = 0.291), and hence, both groups were homogeneous in baseline and at 5th follow-up significant difference (95% CI [30.67–44.18, P = 0.000*]) indicate effectiveness of palliative care bundle in terms of better quality of life of advanced GBC patients in IG over CG.

The baseline mean ZBI score was 68.12 in IG, whereas CG had 71.88 (z = 1.09, P = 0.313), and hence, both groups were homogeneous in baseline ZBI scores. After four months, significant values (z = −8.12, P = 0.000*) indicate the effectiveness of the palliative care bundle in terms of less burden faced by caregivers of IG over CG.

Baseline mean values (95% CI [−0.69–1.31, P = 0.540]) showed that both groups were homogeneous and after 4 months, a significant difference (95% CI [6.03–8.51, P = 0.000*]) showed the effectiveness of palliative care bundle in terms of modified palliative care outcome scale among advanced GBC patients of IG over CG [Table 2].

Comparison of ECOG, pain, and trial outcome index (TOI) scores of IG and CGECOG scores were normally distributed (Kolmogorov– Smirnov Z testing, z = 0.650 and P = 0.792), pain scores showed normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z testing, z = 0.279 and P = 1.000) and TOI scores were normally distributed (Kolmogorov–Smirnov Z testing, z = 0.836 and P = 0.487); hence, independent ‘t’ test used.

At the 5th follow-up after four months, the mean ECOG score was 3.22 ± 0.81 in CG, whereas IG had 1.41 ± 0.77 with 95% CI (1.51–2.10, P = 0.000*), and significant values indicate the effectiveness of palliative care bundle in terms of better performance status of advanced GBC patients in IG over CG.

At four months of follow-ups, the mean pain score was 5.53 ± 0.90 in CG, whereas IG had 2.89 ± 1.11 with 95% CI (2.26–3.01, P = 0.000*), and significant values indicate the effectiveness of the palliative care bundle in terms of betterment of pain reduction among advanced GBC patients in IG over CG.

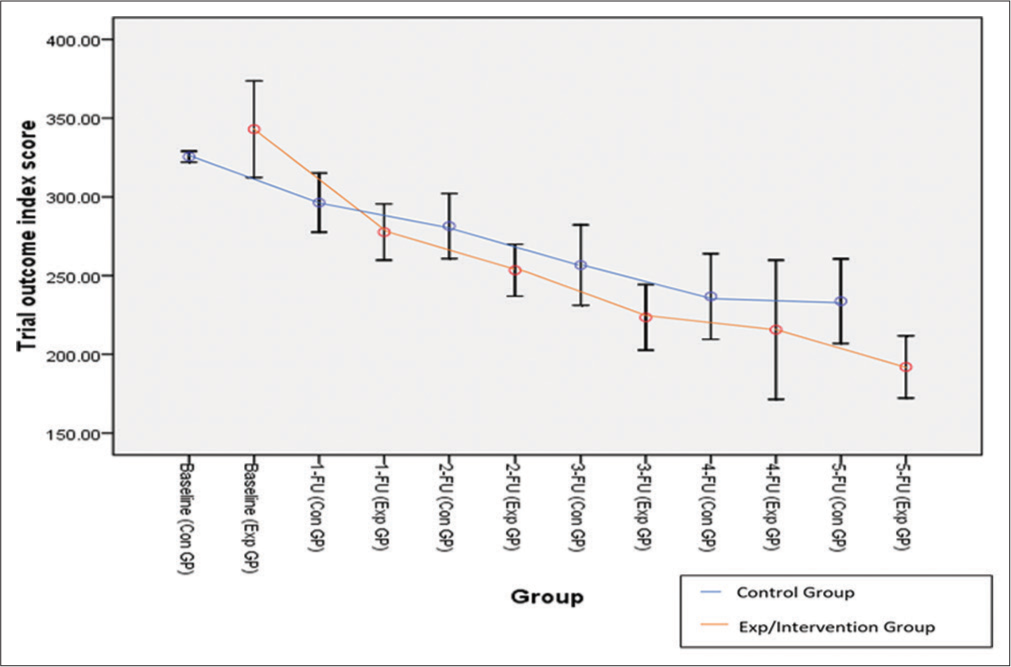

TOI was the total of outcome variables, that is, FIM score, EORTC QLQ, and ZBI score, to check the effectiveness of the palliative care bundle. At the 5th follow-up after four months, the mean TOI score was 233.75 ± 102.08 in CG, whereas IG had 192.0 ± 75.10 with 95% CI (8.79–74.72, P = 0.014*), and the final mean reduction in TOI score was 151 from baseline to 5th follow-up in IG and 91.75 in CG. A significant value (P = 0.014*) of the TOI score indicates the effectiveness of the palliative care bundle among IG over CG [Table 4 and Figure 2].

Table 4: Mean, SD and independent ‘t’ test values.

Variables ECOG Scores Intervention group (n=58) (Mean±SD) Control group (n=58) (Mean±SD) tvalue (P-value) 95% CI (Lower; Upper) ECOG score Baseline 2.17±0.55 2.27±0.55 1.08 (0.279) (−0.08; 0.29) 5th Follow-up 1.41±0.77 3.22±0.81 12.25 (0.0001*) (1.51; 2.10) Pain score Baseline 5.91±0.94 5.82±0.84 −0.52 (0.604) (−0.41; 0.24) 5th Follow-up 2.89±1.11 5.53±0.90 13.97 (0.0001*) (2.26; 3.01) TOI score Baseline 343.0±15.34 325.5±13.25 −1.13 (0.260) (−48.09; 13.09) 5th Follow-up 192.0±75.10 233.75±102.08 2.50 (0.014*) (8.79; 74.72)

Export to PPT

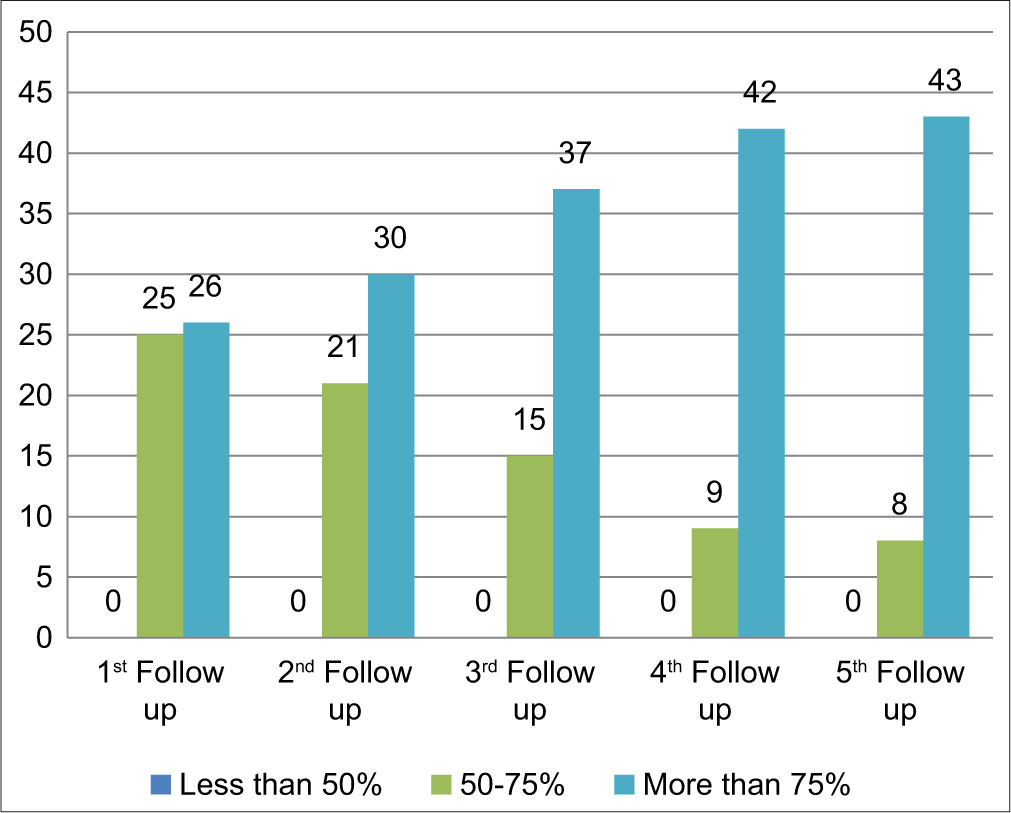

Adherence to palliative care bundleAdherence to the palliative care bundle by IG showed that the majority of patients and caregivers (51%) adhere to 12–14 sessions till 1st follow-up and 18–20 sessions till 2nd (55%), 3rd (63%) and 4th (70%) follow-ups. Most patients and caregivers adhere to 21–23 sessions till the 5th (38%) follow-up; hence, 85% of patients and caregivers showed good adherence to the palliative care bundle [Table 5 and Figure 3].

Table 5: Adherence to palliative care bundle (n=51).

S. No. Follow-up scores <12 12–14 15–17 18–20 21–23 ≥24 n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) n (%) 1. Baseline - - - - - - 2. 1st Follow-up (15) 25 (49) 26 (51) - - - - 3. 2nd Follow-up (30) - 21 (41) 28 (55) 02 (04) - 4. 3rd Follow-up (30) - 15 (30) 32 (63) 04 (07) - 5. 4th Follow-up (30) - 09 (17) 36 (70) 04 (07) 02 (06) 6. 5th Follow-up (30) - 08 (15) 13 (25) 19 (38) 11 (22)

Export to PPT

Reported acceptability of palliative care bundleThe acceptability of the palliative care bundle among IG participants was obtained by acceptability feedback from all 51 participants of IG who completed the study. The acceptability rate of the intervention was 95%. The participants reported acceptability on either of the three-point scale, that is, disagree, agree, or strongly for each item. All the participants (100%) felt that the objective of the intervention was clear to them. Similarly, the majority of the participants (93%) and caregivers (93%) clearly understood the palliative care bundles; 92% felt that it was easy to incorporate palliative care bundles into their daily lives. A majority (96%) reported that the intervention was interesting, and 90% wished to continue the palliative care bundles in the future, and overall, acceptability was 95% [Table 6].

Table 6: Acceptability of palliative care bundle (n=51).

S. No. Items Disagree Agree Strongly agree n(%) n(%) n(%) 1. Was the objective of the intervention clear? 00 (00) 03 (06) 48 (94) 2. Did you clearly understand the PTBD tube care, bhastrika, and Sudarshan kriya 00 (00) 04 (07) 47 (93) 3. Was it easy to incorporate palliative care bundle in your daily life 01 (02) 03 (06) 47 (92) 4. Were you interested in the intervention 00 (00) 02 (04) 49 (96) 5. Do you wish to continue the palliative care bundle practice in future 00 (00) 05 (10) 46 (90) DISCUSSIONGood recruitment (96.7%), fair retention (86.2%), good adherence (85%), high acceptability rates (95%), and no serious side effects suggested that palliative care bundles are feasible, cost-effective and safe for patients and their caregiver who was suffering from advanced GBC. The net mean effect of TOI of IG compared with CG was significant at the 2nd, 3rd, and 5th follow-ups. A significantly good functional independence, better resilience and less burden were faced by caregivers in interventional group at each follow-ups. There was a significant improvement in quality of life in IG with each follow-up. Overall, the modified palliative care outcome scale significantly improved among IG over CG patients. A significant effect of the intervention was observed in ECOG score and pain reduction in each follow-up time, respectively. By last 5th follow-up visit, 85% adherence rate for palliative care bundle was followed by patients and caregivers.

As per the literature search, the researcher did not find any palliative care bundle trial on GBC patients. Hence, the TOI scores of the present study were compared with other advanced cancer patient trials where the baseline mean score was higher in the present study than the study reported by Hlubocky et al.)[27] (343 vs. 102.6, respectively). In the present study, the net effect of intervention with a score of 253.4, 223.46, and 192.0 at 2nd, 3rd, and 5th FU, respectively, exceeded the 3.0 minimal important difference for this scale Trial outcome index indicated better quality of life of patients and less burden faced by caregivers. Consistent with this in the present study, a significant net effect of the palliative care bundle intervention was observed in terms of TOI.

GBC and its treatment-related side effects hamper functional recovery, resilience, and related quality of life and cause a burden on caregivers.[28,29] The linkage between quality of life and physical activity has been firmly established. Physical activity-based non-pharmacological supportive healthcare interventions are promising strategies for improving overall functional recovery, resilience, and related quality of life among advanced GBC patients.[30] In recent years, palliative care has gained popularity among advanced cancer patients as one such adjunct supportive care therapy. The currently available literature supports the usefulness of palliative care supportive care interventions in improving functional recovery, resilience, and related quality of life and reducing the burden on caregivers during and after palliative treatment.

Strength and limitationsSo far, to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has checked the effectiveness of palliative care bundles on functional recovery, resilience, and related quality of life among GBC patients and their caregivers undergoing palliative treatment. Hence, an RCT design was employed in the present study to determine the effect of palliative care bundles on functional recovery, resilience, related quality of life, and other outcome variables. This was a structured palliative care bundle that included problem-solving counselling for patients and caregivers, practicing bhastrika pranayama by patients and Sudarshan kriya by caregivers, symptom management booklet for patients, and demonstration of care of PTBD tube, followed by return demonstrations and need-based re-demonstrations at their regular follow-ups. Emphasis was laid on individualised and regular contact with the participants and their caregivers throughout their palliative treatment. Implementation of the palliative care bundle was feasible and cost-effective as the participants and their caregivers were able to practice it themselves without the use of any costly equipment.

The limitation of this study was due to the nature of the study, blinding was not possible during participant recruitment. Another limitation of the present study was the attrition rate of 13.8%. However, the risk of bias due to it was low as an almost equal dropout rate was noticed in both the study groups (IG: 12%; CG: 15%). Another limitation was that the effect of palliative care bundle intervention on palliative chemotherapy-related side effects, that is, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea and constipation, and other cognitive impairment, were not studied.

The present study was conducted by considering that there was no structured palliative care bundle for advanced cancer patients. Hence, we planned and developed palliative care bundles for functional recovery, resilience, and related quality of life for advanced GBC patients and their caregivers on palliative treatment.

CONCLUSIONPalliative care in India is practiced, but a specialised care needs to be rendered with efficient and cost control both in institutional and community practices. Functional recovery, resilience, and quality of life are often compromised in GBC patients, and their caregivers are always in burden. The study tested a palliative care bundle on patients on a regularly basis at home with help of informational booklet during their entire palliative treatment according to their physical ability. Palliative care bundle provides compelling evidence of its safety, feasibility and effectiveness for improving functional recovery, resilience and quality of life and reducing caregiver burden among advanced GBC patients. Palliative care bundle is also successful in reducing pain and improving performance status along with overall improvement in palliative care outcome. Palliative care bundle intervention was acceptable and found to be interesting by the participants from all socioeconomic backgrounds. The involvement of palliative physicians for motivating and prescribing palliative care bundle intervention enhanced its adherence further. The use of informational booklets also proved as a boon to adherence. Thus, palliative care bundle training may be considered as a supportive care intervention for palliative care settings.

Comments (0)