Head-and-neck cancer is a group of cancers that arise from the oral cavity, oropharynx, larynx, hypopharynx and nasopharynx. They account for a significant global cancer burden, with an annual incidence of more than 750,000 cases and a mortality of around 350,000 per year.[1] Due to the complexity of the anatomy and the function of the sites affected by head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC), these patients experience significant physical, psychological and social problems as a consequence of the disease and its treatment.[2] Patients with HNSCC are particularly prone to psychosocial problems due to the adverse impact of the tumour and its subsequent treatment on their communication and emotional expression.[3] In a hospital-based cross-sectional study on head-and-neck cancer patients, Yadav et al. reported that 49% of the patients had major depressive disorder (MDD), 13% of the patients had MDD with melancholic features, and 10% had dysthymia. The authors concluded that depressive disorders are highly prevalent among head-and-neck cancer patients, and the healthcare team has to be sensitive to this issue.[4]

In addition, the importance of social support cannot be overemphasised as it positively impacts people who have cancer.[5] Social support may be vital in the head-and-neck cancer patient population because this disease may disrupt daily activities due to altered speech, eating and facial aesthetics. Patients with HNSCC report less social support at 12 months post-treatment than they do at the time of diagnosis, and social support-seeking behaviours are the most prevalent strategies for coping among such patients.[6] Some studies have shown that adequate social support benefits patients with head-and-neck cancer in coping with cancer-related symptoms and decreasing anxiety and depression. Social support measures prevent social isolation and ensure that the relationship between the individual and the society is maintained.[2]

Only a limited number of studies from the Indian subcontinent have evaluated the perceived social support and depression among head-and-neck cancer patients.[4,7,8] The aim of the present study was to assess and correlate the perception of social support and the prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms among patients with HNSCC being treated at a major tertiary cancer centre in north India.

MATERIALS AND METHODS Study design and sample size calculationThis cross-sectional study was conducted on 100 patients with HNSCC from October 2020 to July 2021 after the obtainment of ethical clearance from the Institute Ethics Committee. In the context of a pilot study, the sample size was computed using the statistical formula N= 4pq/d2, where p stands for prevalence, d for precision and q is 1-p. With the anticipated prevalence of each of the two outcomes, that is, social support and depression (p) being 50%, the absolute precision (d) being 10%, and the confidence level being 95%, the calculated sample size (4×50× [100–50]/102) was100.

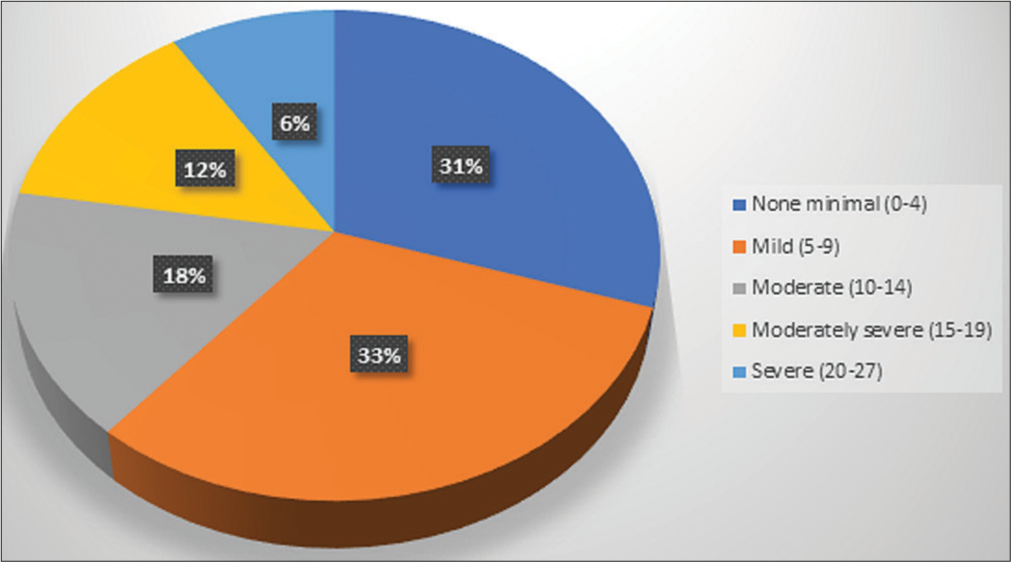

Data collectionPatients with primary HNSCC, aged between 18 and 65 years and able to understand and communicate in Hindi/English language, were enrolled in this study by convenient sampling method. Patients with known psychiatric illnesses were excluded from this study. A total of 105 patients with HNSCC were screened for inclusion in the study. Out of them, five were excluded (two had known psychiatric illnesses, and three did not meet the age inclusion criteria). All patients were explained about the purpose of the study and confidentiality, and informed consent was taken. Subsequently, the clinico-demographic data were collected by a self-structured tool developed by the researchers. Perception of social support was determined by the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS). This is a 12-item standardised, brief, psychometrically sound measure of the subjective assessment of the adequacy of the received emotional and social support from the three sources, that is, family, friends and significant others, developed by Zimet et al. in 1988. Response choices are in the form of a 7-point Likert-type scale, that is, 1- very strongly disagree to 7- very strongly agree. The minimum score of MSPSS is 12, and the maximum possible score is 84. A mean score ranging from 1 to 2.9 is considered low support; a score of 3–5 is considered moderate support, and 5.1–7 is considered high support. The internal consistency of the MSPSS, through Cronbach’s coefficient alpha for the total scale, was 0.87.[9] Depressive symptoms (in the preceding 2 weeks) were assessed using patient health questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), a 9-item questionnaire. The criteria for response choices are 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). The total score of PHQ-9 ranges from 0 to 27. The severity of depressive symptoms is graded as none or minimal (0–4), mild (5–9), moderate (10–14), moderately severe (15–19) and severe (20–27). PHQ-9 items showed good internal (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.85) and test-retest reliability (interclass correlation coefficient = 0.92).[10] The approximate time taken to respond to the questionnaires ranged from 25 to 30 min.

Statistical analysisThe data were analysed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 25.0 using descriptive and inferential statistics. The association between the perception of social support and the clinico-demographic variables was assessed using the Kruskal–Wallis test for three or more groups and the Mann–Whitney test for two groups. The association between the prevalence of depressive symptoms and the clinico-demographic variables was assessed using the Fisher exact test. Karl Pearson’s coefficient of correlation was used to assess the correlation of perception of social support with the prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms. P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTSMost of the HNSCC patients, 37%, were in the 42–54 years age category. A majority of patients, 85%, were male. The two most common subsites involved were the oral cavity (61%) followed by the oropharynx (26%). A significant number of patients, 85%, were diagnosed at an advanced stage (stage III-IV). A family history of cancer was noted in 12% of the patients. More than half, 56%, of the patients were receiving concurrent chemoradiotherapy as the treatment modality at the time of analysis [Table 1].

Table 1: Demographic and clinical profile of the HNSCC patients (n=100).

Variables f (%) Demographic profile Age 18–30 years 6 (6) 30–42 years 21 (21) 42–54 years 37 (37) 54–65 years 36 (36) Gender Male 85 (85) Female 15 (15) Marital status Married 93 (93) Unmarried 5 (5) Others 2 (2) Educational status Illiterate 24 (24) High school certificate 46 (46) Secondary school 15 (15) Graduate or above 15 (15) Occupation Unemployed 74 (74) Employed 12 (12) Others 14 (14) Family income in rupees ≤10,001/month 60 (60) 10,002–29,972/month 26 (26) More than 29,973 14 (14) Place of residence Urban 65 (65) Rural 35 (35) Clinical profile Tumour site Oral cavity 61 (61) Oropharynx 26 (26) Others 13 (13) Time since diagnosis ‘less than 6 months 41 (41) More than 6 months 59 (59) Tumour stage Early-stage (I, II) 15 (15) Advanced stage (III, IV) 85 (85) Comorbid illness Yes 26 (26) No 74 (74) Family history of mental illness Yes 2 (2) No 98 (98) Family history of cancer Yes 12 (12) No 88 (88) Treatment modality being received at the time of analysis Palliative chemotherapy 1 (1) Neoadjuvant chemotherapy 3 (3) Radical radiotherapy 5 (5) Palliative radiotherapy 8 (8) Post-op radiotherapy 15 (15) Surgery 12 (12) Concurrent chemoradiotherapy 56 (56) ECOG PS Good (0–1) 58 (58) Poor (2–4) 42 (42)Only 2% of the patients had low social support, while 38% of the patients had moderate and 60% of the patients had high social support. Among the subscales of the MSPSS, high social support was obtained majorly from the family (98%), followed by significant others (66%) and friends (52%) [Table 2]. There was no statistically significant association of the clinico-demographic variables with the perception of social support, except for the eastern cooperative oncology group (ECOG) performance status (PS) (P = 0.001) [Table 3]. Out of 100 patients, 18% had moderate depressive symptoms, 12% had moderately severe, and 6% had severe depressive symptoms [Figure 1]. A weak negative correlation was found between the perception of social support and the prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms (r = −0.262, P = 0.008). Five categories (none to minimal, mild, moderate, moderately severe and severe) of the PHQ-9 tool were merged into two (minimal to mild and moderate to severe). The association of depressive symptoms with the tumour stage (P = 0.045) and the ECOG PS (P = 0.006) were statistically significant. The other clinico-demographic variables did not show any association with depressive symptoms [Table 4]. Patients with moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms were referred to the psychiatry outpatient department for further evaluation.

Table 2: Subscales of The MSPSS among patients with HNSCC (n=100).

Subscales MSPSS f (%) Family support Low support 1 (1) Moderate support 1 (1) High support 98 (98) Support from significant others Low support 11 (11) Moderate support 23 (23) High support 66 (66) Support from friends Low support 26 (26) Moderate support 22 (22) High support 52 (52)Table 3: Association of the clinico-demographic variables with the perception of social support in patients with HNSCC (n=100).

Variables Perception of social support f (%) Median (IQR) P-value Age 18–30 years 6 (6) 66 (46.5–84) 0.208** 30–42 years 21 (21) 61 (50–84) 42–54 years 37 (37) 71 (59.5–84) 54–65 years 36 (36) 84 (60–84) Gender Male 85 (85) 70 (60–84) 0.963* Female 15 (15) 72 (57–84) Marital status Married 93 (93) 78 (60–84) 0.125** Unmarried 5 (5) 60 (43–76) Widowed 2 (2) 36.5 (12-) Educational status Illiterate 24 (24) 64.5 (53–84) 0.680** High school certificate 46 (46) 81 (60–84) Secondary school 15 (15) 84 (60–84) Graduate or above 15 (15) 63 (57–84) Occupation Unemployed 74 (74) 84 (60–84) 0.614** Employed 12 (12) 62 (58.5–84) Others 14 (14) 71.5 (54.75–84) Family income in rupees ≤10,001/month 60 (60) 67 (53–84) 0.449** 10,002–29,972/month 26 (26) 84 (59.75–84) More than 29,973/month 14 (14) 71 (60.75–84) Place of residence Urban 65 (65) 70 (59.5–84) 0.716* Rural 35 (35) 78 (60–84) Site of tumour Oral cavity 61 (61) 63 (57.5–84) 0.138** Oropharynx 26 (26) 84 (60–84) Others 13 (13) 72 (56–84) Time since diagnosis less than 6 months 41 (41) 84 (60–84) 0.090* More than 6 months 59 (59) 66 (57–84) Tumour stage Early-stage (stage I-II) 15 (15) 61 (53–84) 0.453* Advanced stage (stage III-IV) 85 (85) 72 (60–84) Comorbid illness Yes 26 (26) 64 (55.75–84) 0.427* No 74 (74) 72 (60–84) Family history of cancer Yes 12 (12) 84 (63-84) 0.115* No 88 (88) 68 (57.5-84) Treatment modality Chemotherapy 4 (4) 78 (66.75–84) 0.249** Radiotherapy 28 (28) 62 (52–84) Surgery 12 (12) 65 (58.5–84) Concurrent chemoradiotherapy 56 (56) 84 (60–84) ECOG PS Good (0–1) 58 (58) 84 (60–84) 0.001* Poor (2–4) 42 (42) 60 (49.75–84)

Export to PPT

Table 4: Association of clinico-demographic variables with the self-reported depressive symptoms in patients with HNSCC (n=100).

Variables Self-reported depressive symptoms Minimal to mild (%) Moderate to severe (%) P-value# Age 18–30 years 3 (50) 3 (50) 0.668 30–42 years 12 (57.1) 9 (42.9) 42–54 years 24 (64.9) 13 (35.1) 54–65 years 25 (69.4) 11 (30.6) Gender Male 56 (65.9) 29 (34.1) 0.390 Female 8 (53.3) 7 (46.7) Marital status Married 59 (63.4) 34 (36.6) 0.838 Unmarried 4 (80) 1 (20) Widowed 1 (50) 1 (50) Educational status Illiterate 16 (66.7) 8 (33.3) 0.770 High school certificate 27 (58.7) 19 (41.3) Secondary school 10 (66.7) 5 (33.3) Graduate or above 11 (73.3) 4 (26.7) Occupation Unemployed 46 (62.2) 28 (37.8) 0.062 Employed 11 (91.7) 1 (8.3) Others 7 (50) 7 (50) Family income in rupees ≤10,001/month 36 (60) 24 (40) 0.464 10,002–29,972/month 17 (65.4) 9 (34.6) More than 29,973/month 11 (78.6) 3 (21.4) Place of residence Urban 45 (69.2) 20 (30.8) 0.190 Rural 19 (54.3) 16 (45.7) Tumour site Oral cavity 37 (60.7) 24 (39.3) 0.570 Oropharynx 17 (65.4) 9 (34.6) Others 10 (76.9) 3 (23.1) Time since diagnosis less than 6 months 28 (68.3) 13 (31.7) 0.528 More than 6 months 36 (61) 23 (39) Tumour stage Early stage (stage I-II) 6 (40) 9 (60) 0.045 Advanced stage (stage III-IV) 58 (68.2) 27 (31.8) Comorbid illness Yes 14 (53.8) 12 (46.2) 0.240 No 50 (67.6) 24 (32.4) Family history of cancer Yes 9 (75) 3 (25) 0.529 No 55 (62.5) 33 (37.5) Treatment modality Chemotherapy 3 (75) 1 (25) 0.626 Radiotherapy 15 (53.6) 13 (46.4) Surgery 8 (66.7) 4 (33.3) Concurrent chemoradiotherapy 38 (67.9) 18 (32.1) ECOG PS Good (0–1) 44 (75.9) 14 (24.1) 0.006 Poor (2–4) 20 (47.6) 22 (52.4) DISCUSSIONIn this study of 100 patients with HNSCC, a male preponderance (85%) was noted, typical for an HNSCC cohort.[11,12] Most of them were diagnosed with oral cavity cancer (61%), as reported in other studies.[13-15] The majority of the patients (85%) presented at an advanced stage due to delayed health-seeking behaviour in the Indian subcontinent, reflecting the results of some other studies.[12]

Social support plays a crucial role among patients with cancer, especially of the head and neck, because the site of the tumour itself is distressing, and treatment-related sequelae are also unique to these patients, often leading to impaired communication and emotional expression. In the present study, most of the patients (60%) had overall high social support. These findings are consistent with the results of the studies by Eadie et al. and Ng et al.[13,14] In the social support subscales, the patients received social support mostly from their families, mirroring similar findings from the study by Somasundaram and Devamani.[7] This could be due to the sociocultural structure of the Indian families, where people take more responsibility for looking after their family members. In the present study, the patients with good PS (ECOG PS 0–1) had significantly higher perceptions of social support, reflecting similar findings from the study by Yilmaz et al.[15]

The prevalence of depression (clinical diagnosis or symptoms of depression) among head-and-neck cancer patients is high and depends on the type of measurement tools and the assessment time.[16] In a systematic review, Haisfield-Wolfe et al. reported that over the period, prevalence rates of depression vary from 13 to 40% at diagnosis, 25–52% during treatment and 11–45% in the first 6 months after treatment.[17] In the present cross-sectional study, due to the convenient sampling technique and the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, patients with HNSCC were enrolled irrespective of any specific time point in their illness trajectory, and serial temporal assessments were not done at predefined time points. The prevalence of self-reported moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms (PHQ-9 score of 10–27) was 36% in our study.

It is notable that despite receiving high social support (60% of patients), there was still a high prevalence of self-reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms (36% of patients) in the current study. A weak negative correlation (P = 0.008) was found between the perception of social support and the prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms. This suggests that social support alone may not be sufficient to alleviate depressive symptoms in this population, and additional interventions may be needed to address mental health concerns. A plethora of studies have demonstrated that higher social support is significantly associated with less depressive symptoms and a higher general mental health score.[3,6,18-20] However, in the study by Katz et al. on multiple regression analysis, social support was not related to depressive symptoms in surgically treated patients with HNSCC.[21]

A higher locoregional disease burden in patients with stage III-IVB HNSCC may result in increased difficulty in eating, swallowing, pain, discomfort and sleeping issues reflected by a relatively higher prevalence of depression.[22] However, on subgroup analysis in the present study, the prevalence of moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms was 60% versus 31.8% in patients with early and advanced stages, respectively. This paradoxical result may be attributed to the relatively low number of patients with early-stage cancer (15%) in this study. In addition, the patients with poor PS (ECOG PS 2–4) were significantly more likely to have moderate-to-severe depressive symptoms in this study. This is in concordance with the results of studies by Yadav et al. and Hammerlid et al.[4,23] Further, this may be explained by the fact that patients with HNSCC, who have a considerable limitation of day-to-day activity, are more likely to be diagnosed with psychological distress, MDD and melancholic features.

Relative heterogeneity pertaining to the sites of HNSCC, the different treatment modalities, the time points of assessment of perception of social support and the prevalence of self-reported depressive symptoms, and the lack of temporal assessment of these parameters at predefined time points (e.g. before, during and after treatment) are some of the limitations of this cross-sectional study, which was conducted in challenging circumstances amidst the resource limitations of a tertiary cancer centre in a low-middle income country during an ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. The convenience sampling method used in this study might have introduced selection bias and limited the generalisability of the findings. We relied on self-reported measures of depressive symptoms, which may not accurately reflect the true prevalence of depression in the study population. Objective assessment of depression by clinical interviews or diagnostic assessments, alongside self-reported data, may provide a more accurate estimate of the prevalence of depression. Finally, the cross-sectional design of our study limits the ability to establish causal relationships between social support and depressive symptoms.

Based on the study results, we recommend the implementation of routine screening for depression in patients with HNSCC with high symptom burden using validated assessment tools, followed by personalised intervention plans. These interventions may include cognitive behavioural therapy, pharmacological treatments and psychoeducation to help patients manage their symptoms effectively. Future directions for improving mental health support in patients with HNSCC could involve (a) enhanced screening protocols: regular and systematic screening for mental health issues at various stages of cancer treatment to ensure timely intervention; (b) multidisciplinary approaches: collaboration between oncologists, psychiatrists, psychologists and social workers to create a holistic treatment plan that addresses both physical and mental health needs; (c) patient education: providing resources and information to patients and their families about the psychological impact of cancer and available support services; (d) telehealth services: expanding access to mental health support through telehealth platforms, especially for patients in remote areas or those with mobility challenges and (e) research and training: conducting further research on the mental health needs of such patients and training healthcare providers to recognise and address these needs effectively.

CONCLUSIONDespite receiving high social support, there was a high prevalence of self-reported moderate to severe depressive symptoms in patients with HNSCC in north India. These findings emphasise the need for targeted mental health monitoring and rehabilitation and underscore the importance of a multidisciplinary approach to cancer care that addresses the psychological and social needs of patients, particularly those with high symptom burden.

Comments (0)