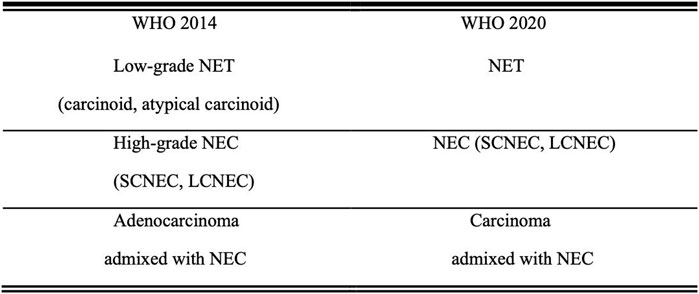

NENs are both aggressive and rare [1]. According to the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database, NETs are most commonly found in the lungs, followed by the gastrointestinal system and pancreas. They can also occur in unknown primary lesions, which may include the uterine cervix [2]. Cervical NEC has a high malignancy rate, a high fatality rate, and a poor prognosis. This type of cancer shares characteristics with NETs and can grow locally or spread to other regions of the body [3]. In Japan, newly diagnosed cervical NEC accounts for 1.6 percent of all instances of cervical cancer. SCNEC accounts for 1.3 percent of this total, while LCNEC accounts for 0.3 percent [4]. This is consistent with existing data that SCCC is more common than LCCC in cervical NEC [5, 6]. As the disease is uncommon in the female reproductive system, the 2020 WHO classification of NENs (Figure 1) categorizes them into two groups: neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) and neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs), which is different from the 2014 WHO classification of NENs [7]. The terms “low-grade NET” and “high-grade NEC” have been removed from the new categorization. Considering that NECs are frequently linked to adenocarcinoma, the term “Carcinoma admixed with NEC” has been preserved in the 2020 WHO classifications of NENs [8].

FIGURE 1. Comparison of the 2014 and 2020 WHO classifications of NENs Abbreviations: NET, neuroendocrine tumor; NEC, neuroendocrine carcinoma; SCNEC, small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma; LCNEC, large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma.

HPV infections are related to cervical NEC, specifically with the HPV strains 16, 18, or 35 [9–11]. This is partly because HPV E6 protein breaks down the p53 protein and reduces its production. Moreover, Kasuga found that 72 percent were complicated by high-risk HPV infection (14% HPV16% and 86% HPV18) [12]. In addition, P16INK4A expression is frequently increased in high-risk HPV infections associated with cervical NEC [13]. Argyrophilic cells are created when pluripotent stem cells differentiate into neuroendocrine cells in the mucosal epithelium. These cells may produce endocrine hormones. However, most cervical NEC patients have clinically absent neuroendocrine symptoms, indicating that the tumor either secretes insufficient hormones or produces hormones that are quickly deactivated in the blood [14]. Given the limited treatment options, cervical NEC is prone to early local diffusion and distant metastasis, with high malignancy and death rate and poor prognosis. According to Margolis [15], the risk of death for early-stage small cell cervical NEC (stages IA-IIA) was 2.96 times higher than that for early-stage squamous cell cervical cancer. The prognosis for cervical NEC is quite grim, with a mean recurrence-free survival of only 16 months and a mean overall survival of 40 months [16]. The survival rate over a 5 years period is less than 35%. The likelihood of a poor prognosis is higher for those with advanced stages, high-grade tumors, and a lack of treatment options such as surgery, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy [17, 18]. Additionally, smoking, a cumulative radiation dose (EQD2) of 50 gy, and the absence of brachytherapy have been linked to the recurrence of cervical NEC [19].

PathologyCervical NEC can manifest as an erosive, cauliflower-shaped, or ulcer-like growth. It is usually gray-white or gray-yellow and can penetrate within the cervix to become barrel-shaped, similar to squamous or adenocarcinoma. Under a microscope, the cells have characteristics similar to small-cell lung cancer, but there are some differences. The cells are uniformly small and contain few cytoplasmic components. Tumor cells are often microscopic or intermediate in size and can infiltrate solid sheets or structures that resemble spinal cords. Both mitosis and necrosis are typical and common. However, the nuclei of SCNEC are quite large, densely hyperchromatic, and have unclear nucleoli that are often accompanied by necrosis [20, 21]. Cervical NEC can develop in association with adenocarcinoma or squamous carcinoma, resulting in distal necrosis of squamous or adenocarcinoma cells and invasion of the lymphatic and vascular systems [22].

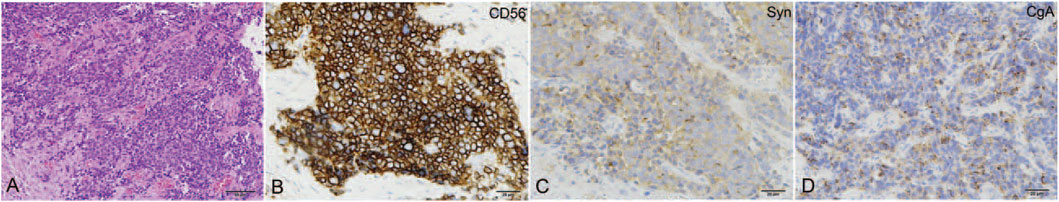

According to reports, the neuroendocrine staining agents commonly used are chromogranin A (CgA), synaptophysin (SYN), CD56, and neuron-specific enolase (NSE). However, it has been observed that cervical SCNEC does not always react to these neuroendocrine staining agents, including CgA, SYN, and NSE (Figure 2) [23]. Tempfer discovered that the positive rate of Syn (424/538; 79%), NSE (196/285; 69%), CHR (323/486; 66%), and CD56 (162/267; 61%) in cervical NEC [16]. Various immunological markers have varying degrees of sensitivity and specificity. For example, CD56 possesses a high sensitivity but a low specificity. Consequently, it is preferable to use a combination of IHC markers as opposed to a single marker [20]. For cervical NEC, SYN in conjunction with CD56 is far more dependable. Huang found that the positive rate of Syn and CD56 was 87.75% (82.03%–93.87%, 33.3%), which was higher than the positive rates of Syn and NSE (50.50%–87.68%, 82.7%) and Syn and CgA (53.33%–76.98%, 73.5%) [24]. INSM1 is a new immunological marker that is highly sensitive and specific as a nuclear immune marker [25]. Research has shown that INSM1 has a higher sensitivity than CHR, is equivalent to Syn but lower than CD56, and has a higher specificity than Syn. INSM1 contains unique dots that are not present in typical immune chemicals. For instance, INSM1 is activated when traditional neuroendocrine indicators are difficult to interpret due to obvious squeezing artifacts or acute necrosis in the presence of complement cytoplasmic or membrane staining. As INSM1 is primarily associated with gastrointestinal tumors, it can assist in determining the tumor’s tissue-specific origin as well as the starting point of the metastatic neuroendocrine tumor [26].

FIGURE 2. The pathological features of cervical NEC. (A) The tumor was composed of small round cells arranged in the nest-like structure (HE, ×200); the tumor cell showed positive for CD56 (B), Syn (C), and CgA (D). Reproduced from ref. 21 with permission, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0.

DiagnosisCervical NEC can be diagnosed through various methods, including clinical symptoms, radiographic and nuclear imaging, and histopathology. The symptoms of cervical NEC include ectopic neuroendocrine secretion, such as Cushing syndrome, carcinoid syndrome, hypoglycemia, syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion (SIADH), and hypercalcemia, as well as stomach discomfort. According to Zhao, hyponatremia caused by SIADH is not a good predictor of prognosis and may be used to predict partial recurrence [14]. However, not all patients with cervical NEC will experience symptoms of ectopic neuroendocrine secretion. Instead, most patients may experience abnormal cervical smear, pelvic mass, irregular vaginal bleeding, or postmenopausal vaginal bleeding [27]. Very few cases have been reported where the individual displayed no symptoms. As an invasive illness, cervical NEC may cause distant metastases and systemic symptoms. During a specialist examination, an external cervical tumor may be detected [28], while periuterine thickening or nodules may be found during a triad examination.

Pelvic MRI is better than CT scans for detecting cervical NEC because it has higher soft tissue resolution and can better measure tumor size and local infiltration [29]. However, scar tissue and remaining tumor tissue may have identical signal strengths, affecting MRI accuracy in cervical NEC recurrence. Thus, PET-CT and pelvic MRI complement clinical staging and recurrence. Research shows that the 18F-FDG PET/CT scan is crucial for staging cervical NEC because hematogenous spread can occur early. This scan can detect lymph node involvement or early hematogenous dissemination, changing FIGO staging. Additionally, the 18F-FDG PET/CT scan can detect local recurrence and evaluate therapy response after clinical operations [30].

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) is essential for cervical NEC diagnosis. First, IHC properly replicates the tumor’s origin, which is crucial for diagnosis. Second, IHC can identify squamous and glandular epithelial components, helping determine the cervical NEC’s type [31]. SYN, NSE, CgA, and CD56 are considered classic neuroimmune markers. The majority of cervical NECs contain at least one of these immunological markers.

It is important to differentiate cervical NEC from basal-like squamous-cell carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma of the lower uterine segment, rhabdomyosarcoma, and metastatic carcinoma. Cervical NEC can be distinguished from basal-like squamous-cell carcinoma by the fact that the nuclei are not compressed or tightly packed together. Despite this, undifferentiated lower uterine cancer is difficult to recognize due to the presence of neuroendocrine and immunological markers [32]. Rhabdomyosarcoma can be distinguished from cervical NEC by the presence of myogenin and Myo-D1.

Gene SequencingThe majority of targeted area sequencing, whole-exome sequencing (WES), and whole-genome sequencing (WGS) are facilitated by Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) technology. Using these strategies, previously undiscovered genes can be located. Gene mutations are the effective therapeutic targets that can be pursued. PIK3CA, KRAS, PTEN, and TP53 mutations have been identified as the most prevalent cervical NEC mutations [33–35]. Using NGS, wen found a PTEN mutation in one of two cervical NEC patients [36]. Eskander discovered that out of 97 patients with High-grade neuroendocrine cervical cancer (HGNEC), 83 (85.6%) had high-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) strains, mainly HPV 16 and 18. In a genomic analysis of HGNEC, the most common mutations were PIK3CA (19.6%), MYC (15.5%), TP53 (15.5%), and PTEN (14.4%). Gene genomic alterations (GAs) of PIK3CA, TP53, PTEN, ARID1A, and RB1 were associated with HPV. Interestingly, it was found that GAs were more common in the HPV-negative group than in the HPV-positive group. The HGNEC GAs included the PI3K/AKT/mTOR (41.2%), Ras/MEK (11.3%), homologous recombination (9.3%), and Erbb (7.2%) pathways. Notably, among the 97 patients, only 2.1% had a high tumor mutation burden (TMB) with both MSH2 mutations, while 16.5% had an intermediate TMB [37]. However, Microsatellite instability (MSI) is less prevalent than TP53 [38]. Soo further demonstrated that genes in the ATRX, ERBB4, and AKT/mTOR pathways were most frequently altered by WES, signaling that ERBB4-Akt/mTOR inhibitors may be a viable new anticancer treatment option for patients with cervical NEC [39]. In instances of recurrent cervical NEC, the genes associated with DNA mismatch repair (MMR) systems and MYC, TP53, KRAS, and the PI3K-AKT pathway are most likely to be altered [40, 41].

Multimodality TherapyDue to the rarity of cervical NEC, treatment options are primarily based on other malignant neuroendocrine tumors outside of the genital tract, as well as common cervical squamous or adenocarcinoma. Currently, multimodal therapy combining surgery, radiation, chemotherapy, targeted therapy, and immunotherapy is the mainstream [42, 43]. However, there is currently no standard treatment for cervical NEC.

Early treatment for malignancies smaller than 4 cm in diameter typically involves radical hysterectomy, regional lymphadenectomy, and postoperative adjuvant therapy. Ishikawa revealed that out of 93 patients with stage I-II high-grade cervical NEC, 88 underwent radical surgery as their initial treatment, while only 5 patients received radiation. In the surgical group, 37 patients received radical surgery and pelvic lymphadenectomy in conjunction with postoperative chemotherapy, 14 received surgery alone, and 25 received surgery with adjuvant or neoadjuvant chemotherapy before the procedure. The mortality hazard ratio in the group exposed to direct radiation was 4.74 (95% confidence interval: 1.01–15.9). The surgical group’s overall survival rate was greater than that of the direct radiation group (p = 0.043) [44]. However, Stecklein reported that concurrent chemoradiotherapy is more effective than surgery in treating early-stage cervical NEC with negative lymph node metastasis [45].

For malignancies larger than 4 cm in diameter, some medical professionals recommend using chemoradiotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery [46, 47]. Research reported that 2018 patients diagnosed with HGNEC at pathological stages IA2 to IIIC2 underwent primary surgery. The 5 years overall survival rate for patients in Stage I, II, and III was 84.9%, 85.7%, and 60.9%, respectively. The Kaplan-Meier survival curves indicated that there was no significant difference in overall survival and progression-free survival between patients who received postoperative chemoradiotherapy and those who only received chemotherapy (overall survival: p = 0.77; progression-free survival: p = 0.41) [48]. However, it is common to treat this type of cancer with a combination of chemotherapy and radiation. From 1998 to 2002, eight patients with stage III/IV cervical NEC were treated with etoposide and Cisplatin in conjunction with external irradiation and intracavitary brachytherapy at the Columbia Cancer Agency. The three-year survival rate for advanced-stage cervical NEC is expected to be 38%–40% [49]. In addition, protecting fertility is crucial for women of reproductive age. Cervical NEC is a deadly cancer with limited treatment options, so the NCCN does not recommend preserving reproductive function [23].

The guidelines for chemotherapy recommend using either Etoposide-Cisplatin (EP) or vincristine, dactinomycin, and cyclophosphamide (VAC). Studies have shown that EP is less toxic than VAC. In addition, the EP, TP, or TC regimen has been proven effective in specific clinical situations [50, 51]. However, Wang discovered that the combination of etoposide and platinum did not result in an improved overall survival rate after surgery when compared to the combination of platinum and paclitaxel (p = 0.71). The univariate analysis showed that patients who received chemotherapy with four or more cycles had a better prognosis than those who received less than four cycles (OS: p = 0.01; HR = 6.71; PFS: p = 0.02; HR = 5.18). Furthermore, the multivariate analysis indicated that the number of chemotherapy cycles (p = 0.02; HR = 0.29) was a prognostic factor for PFS [48]. In addition, chemotherapy can increase the amount of antigens released by immunosuppressive tumor cells upon their death, thereby enhancing the efficacy of immunotherapy. Combining immunotherapy with chemoradiation can have a synergistic effect with less effort. Frumovitz found that the TPB regimen, which combines bevacizumab, paclitaxel, and cisplatin, outperformed non-TPB regimens in terms of progression-free survival and overall survival [52]. The combination of EP and the PI3K inhibitor bez235 significantly slowed the proliferation of HM-1 cells, and cervical NEC cell lines exhibited greater cytotoxic responses due to decreased cell viability and increased apoptosis [53].

Radiotherapy is crucial for treating advanced stages of cervical NEC. Based on the SEER data, Zhang discovered that the median survival time for the surgery group was 44.6 months, while it was 80.9 months for the surgery plus radiotherapy group. However, Radiotherapy should be used with caution when there is no metastasis present [54], as the addition of radiotherapy to surgery did not show significant differences compared to surgery alone (p = 0.146) [55].

The recurrence of cervical NEC remains a major troublesome clinical problem. Mabuchi discovered that the initial occurrence of recurrent small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma of the cervix was effectively treated through robot-assisted ultra-radical hysterectomy. While this case firstly exemplifies the security and feasibility of robot-assisted SRH, the extent to which minimally invasive surgery should be utilized in all patients with recurrent cervical cancer remains uncertain [56]. The options for treating relapses of cervical NEC using traditional methods are limited. However, the use of immune checkpoint inhibitors provides hope for patients [19]. Ji discovered that out of the 20 cervical NEC patients tested, 14 (70%) were positive for programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and 15 (75%) were positive for poly ADP-ribose polymerase-1 (PARP1) [38]. The high sensitivity of cervical NEC to PD-L1 and PARP1 suggests that inhibitors for PD-L1 and PARP1, as well as their combination, may provide a novel treatment strategy for cervical NEC. One patient with a second recurrence of stage IIIC1 cervical NEC responded very well to tislelizumab treatment, showing a marked reduction in both supraclavicular lymph nodes and retroperitoneal masses after 3 months of treatment. Thus, Patients with recurrent cervical NEC should undergo molecular testing, such as PD-L1 and MMRs, for personalised treatment.

ConclusionCervical NEC is a rare and aggressive disease with a mean overall survival of 46.3 months [55]. Ectopic secretion is more frequently observed in small-cell lung cancer and gastrointestinal neuroendocrine tumors, whereas the symptoms of ectopic secretion are rare in cervical NEC. The prognosis of cervical NEC is affected by the status of HPV infection, chemotherapy cycles and metastasis. Immunological markers such as Syn NSE, CgA, and CD56, as well as newer markers like INSM1, have shown high sensitivity and specificity in detecting cervical NEC. Currently, there are no ongoing prospective clinical trials for the treatment of cervical NEC; instead, the available studies are mainly retrospective. The choice of postoperative adjuvant therapy varies among oncologists. Adjuvant therapy may involve systemic chemotherapy alone or a combination of therapies, such as concurrent systemic chemotherapy with radiotherapy (CCRT) or sequential chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy. Due to the highly invasive nature of the disease, fertility preservation is generally not recommended in clinical practice. However, further research is necessary to determine the best course of action. In recent years, the development of gene sequencing has provided new targets for targeted therapy, which has helped patients who are experiencing recurrence. In addition to surgery, chemoradiotherapy, and immunotherapy, electric field therapy is being evaluated as an adjuvant treatment for malignancies that have become more aggressive in recent years. Tumor Treating Fields (TTFields) operate on tubulin to suppress spindle formation and tumor cell mitosis [57]. The Phase 2 INNOVATE clinical trial [NCT02244502] confirmed the safety of TTFields combined with weekly paclitaxel in 31 patients with platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (PROC). The progression-free survival (PFS) for TTFields in combination with weekly paclitaxel was 8.7 months, compared to 4.1 months for earlier chemotherapeutic regimens [58]. Therefore, further scientific and clinical research is required to determine if the potential therapeutic benefits of electric field therapy for highly invasive neuroendocrine tumors can be achieved. In the future, additional research and in-depth studies are required to ascertain the biological behavior of these uncommon tumors and develop a treatment strategy that is feasible for them.

Author ContributionsXR drafted the work and performed the research. GW conceived the idea and revised and corrected the final version. WW revised the manuscript. QL and WL drew the figures. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Conflict of InterestThe authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

AcknowledgmentsThe authors thank the application of indocyanine green fluorescence-guided laparoscopic retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy in the surgical and pathological staging of early cervical cancer (S20015).

References1. Satoh, T, Takei, Y, Treilleux, I, Devouassoux-Shisheboran, M, Ledermann, J, Viswanathan, AN, et al. Gynecologic Cancer InterGroup (GCIG) Consensus Review for Small Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix. Int J Gynecol Cancer (2014) 24(9):S102–S108. doi:10.1097/igc.0000000000000262

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Dasari, A, Shen, C, Halperin, D, Zhao, B, Zhou, S, Xu, Y, et al. Trends in the Incidence, Prevalence, and Survival Outcomes in Patients With Neuroendocrine Tumors in the United States. JAMA ONCOLOGY (2017) 3(10):1335–42. doi:10.1001/jamaoncol.2017.0589

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Appetecchia, M, Benevolo, M, and Mariani, L. Neuroendocrine Small-Cell Cervical Carcinoma. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol (2001) 96(1):128–31. doi:10.1016/s0301-2115(00)00409-7

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

4. Nagase, S, Ohta, T, Takahashi, F, and Enomoto, T. Annual Report of the Committee on Gynecologic Oncology, the Japan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology: Annual Patients Report for 2015 and Annual Treatment Report for 2010. J Obstet Gynaecol Res (2019) 45(2):289–98. doi:10.1111/jog.13863

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

5. Albores-Saavedra, J, Gersell, D, Gilks, CB, Henson, DE, Lindberg, G, Santiago, H, et al. Terminology of Endocrine Tumors of the Uterine Cervix: Results of a Workshop Sponsored by the College of American Pathologists and the National Cancer Institute. Arch Pathol Lab Med (1997) 121(1):34–9.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

6. Van Nagell, JR, Donaldson, ES, Wood, EG, Maruyama, Y, and Utley, J. Small Cell Cancer of the Uterine Cervix. Cancer (1977) 40(5):2243–9. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(197711)40:5<2243::aid-cncr2820400534>3.0.co;2-h

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

8. RJ Kurman, ML Carcangiu, CS Herrington, and RH Young, editors. WHO Classification of Tumours of Female Reproductive Organs. 4th ed. Lyon, France: IARC Press (2014).

9. Stoler, MH, Mills, SE, Gersell, DJ, and Walker, AN. Small-Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Cervix. A Human Papillomavirus Type 18-Associated Cancer. Am J Surg Pathol (1991) 15(1):28–32. doi:10.1097/00000478-199101000-00003

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

10. Seiwert, TY, Burtness, B, Mehra, R, Weiss, J, Berger, R, Eder, JP, et al. Safety and Clinical Activity of Pembrolizumab for Treatment of Recurrent or Metastatic Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the Head and Neck (KEYNOTE-012): An Open-Label, Multicentre, Phase 1b Trial. Lancet Oncol (2016) 17(7):956–65. doi:10.1016/s1470-2045(16)30066-3

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. Schultheis, AM, de Bruijn, I, Selenica, P, Macedo, GS, da Silva, EM, Piscuoglio, S, et al. Genomic Characterization of Small Cell Carcinomas of the Uterine Cervix. Mol Oncol (2022) 16(4):833–45. doi:10.1002/1878-0261.12962

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

12. Kasuga, Y, Miyakoshi, K, Nishio, H, Akiba, Y, Otani, T, Fukutake, M, et al. Mid-Trimester Residual Cervical Length and the Risk of Preterm Birth in Pregnancies After Abdominal Radical Trachelectomy: A Retrospective Analysis. BJOG (2017) 124(11):1729–35. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.14688

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

13. Ta, TV, Nguyen, QN, Truong, VL, Tran, TT, Nguyen, HP, and Vuong, LD. Human Papillomavirus Infection, p16INK4a Expression and Genetic Alterations in Vietnamese Cervical Neuroendocrine Cancer. Malaysian J Med Sci (2019) 26(5):151–7. doi:10.21315/mjms2019.26.5.15

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

14. Zhao, CF, Zhao, SF, and Du, ZQ. Small Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix Complicated by Syndrome of Inappropriate Antidiuretic Hormone Secretion: A Case Report. J Int Med Res (2021) 49(2):030006052098565. doi:10.1177/0300060520985657

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

15. Margolis, B, Tergas, AI, Chen, L, Hou, JY, Burke, WM, Hu, JC, et al. Natural History and Outcome of Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Cervix. Gynecol Oncol (2016) 141(2):247–54. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.02.008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

16. Tempfer, CB, Tischoff, I, Dogan, A, Hilal, Z, Schultheis, B, Kern, P, et al. Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Cervix: A Systematic Review of the Literature. BMC Cancer (2018) 18(1):530. doi:10.1186/s12885-018-4447-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

17. Li, Q, Yu, J, Yi, H, and Lan, Q. Distant Organ Metastasis Patterns and Prognosis of Neuroendocrine Cervical Carcinoma: A Population-Based Retrospective Study. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) (2022) 13:924414. doi:10.3389/fendo.2022.924414

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

18. Ishikawa, M, Kasamatsu, T, Tsuda, H, Fukunaga, M, Sakamoto, A, Kaku, T, et al. A Multi-Center Retrospective Study of Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Uterine Cervix: Prognosis According to the New 2018 Staging System, Comparing Outcomes for Different Chemotherapeutic Regimens and Histopathological Subtypes. Gynecol Oncol (2019) 155(3):444–51. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2019.09.018

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

19. Bajaj, A, Frumovitz, M, Martin, B, Jhingran, A, Albuquerque, KV, Yen, A, et al. Small Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix: Definitive Chemoradiation for Locally Advanced Disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (2018) 102(3):S85-S86. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.06.226

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

21. Liu, H, Zhang, Y, Chang, J, Liu, Z, and Tang, N. Differential Expression of Neuroendocrine Markers, TTF-1, P53, and Ki-67 in Cervical and Pulmonary Small Cell Carcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) (2018) 97(30):e11604. doi:10.1097/md.0000000000011604

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

22. Zhou, J, Wu, SG, Sun, JY, Tang, LY, Lin, HX, Li, FY, et al. Clinicopathological Features of Small Cell Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix in the Surveillance,epidemiology,and End Results Database. Oncotarget (2017) 8:40425–33. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.16390

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

23. Conner, MG, Richter, H, Moran, CA, Hameed, A, and Albores-Saavedra, J. Small Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix: A Clinicopathologic and Immunohistochemical Study of 23 Cases. Ann Diagn Pathol (2002) 6(6):345–8. doi:10.1053/adpa.2002.36661

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

24. Huang, R, Yu, L, Zheng, C, Liang, Q, Suye, S, Yang, X, et al. Diagnostic Value of Four Neuroendocrine Markers in Small Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Cervix: A Meta-Analysis. Sci Rep (2020) 10(1):14975. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-72055-x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

25. Horn, LC, Hentschel, B, Bilek, K, Richter, CE, Einenkel, J, and Leo, C. Mixed Small Cell Carcinomas of the Uterine Cervix: Prognostic Impact of Focal Neuroendocrine Differentiation But Not of Ki-67 Labeling Index. Ann Diagn Pathol (2006) 10(3):140–3. doi:10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2005.07.019

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

26. Juhlin, CC, Zedenius, J, and Höög, A. Clinical Routine Application of the Second-Generation Neuroendocrine Markers ISL1, INSM1, and Secretagogin in Neuroendocrine Neoplasia: Staining Outcomes and Potential Clues for Determining Tumor Origin. Endocr Pathol (2020) 31(4):401–10. doi:10.1007/s12022-020-09645-y

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

27. D'Antonio, A, Addesso, M, Caleo, A, Guida, M, and Zeppa, P. Small Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Endometrium With Pulmonary Metastasis: A Clinicopathologic Study of a Case and a Brief Review of the Literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond) (2016) 5:114–7. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2015.12.055

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

28. Madžarac, V, Culej, D, Mužinić, D, Zovko, G, Fenzl, V, and Duić, Ž. Small-Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Cervix Associated With Adenocarcinoma in Situ: A Case Report With Analysis of Molecular Abnormalities. Neuro Endocrinol Lett (2023) 44(5):332–5.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

29. Sala, E, Rockall, AG, Freeman, SJ, Mitchell, DG, and Reinhold, C. The Added Role of MR Imaging in Treatment Stratification of Patients With Gynecologic Malignancies: What the Radiologist Needs to Know. Radiology (2013) 266:717–40. doi:10.1148/radiol.12120315

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

30. Lin, Y, Lin, WY, Liang, JA, Lu, YY, Wang, HY, Tsai, SC, et al. Opportunities for 2-[(18)F] Fluoro-2-Deoxy-D-Glucose PET/CT in Cervical-Vaginal Neuroendocrine Carcinoma: Case Series and Literature Review. Korean J Radiol (2012) 13(6):760–70. doi:10.3348/kjr.2012.13.6.760

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

31. Atienza-Amores, M, Guerini-Rocco, E, Soslow, RA, Park, KJ, and Weigelt, B. Small Cell Carcinoma of the Gynecologic Tract: A Multifaceted Spectrum of Lesions. Gynecol Oncol (2014) 134(2):410–8. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2014.05.017

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

32. Masuda, K, Banno, K, Yanokura, M, Kobayashi, Y, Kisu, I, Ueki, A, et al. Carcinoma of the Lower Uterine Segment (LUS): Clinicopathological Characteristics and Association With Lynch Syndrome. Curr Genomics (2011) 12(1):25–9. doi:10.2174/138920211794520169

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

33. Takayanagi, D, Hirose, S, Kuno, I, Asami, Y, Murakami, N, Matsuda, M, et al. Comparative Analysis of Genetic Alterations, HPV-Status, and PD-L1 Expression in Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Cervix. Cancers (Basel) (2021) 13(6):1215. doi:10.3390/cancers13061215

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

34. Frumovitz, M, Burzawa, JK, Byers, LA, Lyons, YA, Ramalingam, P, Coleman, RL, et al. Sequencing of Mutational Hotspots in Cancer-Related Genes in Small Cell Neuroendocrine Cervical Cancer. Gynecol Oncol (2016) 141(3):588–91. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.04.001

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

35. Hillman, RT, Cardnell, R, Fujimoto, J, Lee, WC, Zhang, J, Byers, LA, et al. Comparative Genomics of High Grade Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Cervix. PLoS One (2020) 15(6):e0234505. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0234505

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

36. Wen, H, Guo, QH, Zhou, XL, Wu, XH, and Li, J. Genomic Profiling of Chinese Cervical Cancer Patients Reveals Prevalence of DNA Damage Repair Gene Alterations and Related Hypoxia Feature. Front Oncol (2021) 11:792003. doi:10.3389/fonc.2021.792003

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

37. Eskander, RN, Elvin, J, Gay, L, Ross, JS, Miller, VA, and Kurzrock, R. Unique Genomic Landscape of High-Grade Neuroendocrine Cervical Carcinoma: Implications for Rethinking Current Treatment Paradigms. JCO Precis Oncol (2020) 4:PO.19.00248. doi:10.1200/PO.19.00248

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

38. Ji, X, Sui, L, Song, K, Lv, T, Zhao, H, and Yao, Q. PD-L1, PARP1, and MMRs as Potential Therapeutic Biomarkers for Neuroendocrine Cervical Cancer. Cancer Med (2021) 10(14):4743–51. doi:10.1002/cam4.4034

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

39. Cho, SY, Choi, M, Ban, HJ, Lee, CH, Park, S, Kim, H, et al. Cervical Small Cell Neuroendocrine Tumor Mutation Profiles via Whole Exome Sequencing. Oncotarget (2017) 8(5):8095–104. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.14098

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

41. Schwarz, JK, Payton, JE, Rashmi, R, Xiang, T, Jia, Y, Huettner, P, et al. Pathway-Specific Analysis of Gene Expression Data Identifies the PI3K/Akt Pathway as a Novel Therapeutic Target in Cervical Cancer. Clin Cancer Res (2012) 18(5):1464–71. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-11-2485

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

42. Sevin, BU, Method, MW, Nadji, M, Lu, Y, and Averette, HA. Efficacy of Radical Hysterectomy as Treatment for Patients With Small Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix. Cancer (1996) 77(8):1489–93. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0142(19960415)77:8<1489::aid-cncr10>3.0.co;2-w

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

43. Ku, JW, Zhang, DY, Song, X, Li, XM, Zhao, XK, Lv, S, et al. Characterization of Tissue Chromogranin A (CgA) Immunostaining and Clinicohistopathological Changes for the 125 Chinese Patients With Primary Small Cell Carcinoma of the Esophagus. Dis Esophagus (2017) 30(8):1–7. doi:10.1093/dote/dox041

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

44. Ishikawa, M, Kasamatsu, T, Tsuda, H, Fukunaga, M, Sakamoto, A, Kaku, T, et al. Prognostic Factors and Optimal Therapy for Stages I-II Neuroendocrine Carcinomas of the Uterine Cervix: A Multi-Center Retrospective Study. Gynecol Oncol (2018) 148(1):139–46. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2017.10.027

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

45. Stecklein, SR, Jhingran, A, Burzawa, J, Ramalingam, P, Klopp, AH, Eifel, PJ, et al. Patterns of Recurrence and Survival in Neuroendocrine Cervical Cancer. Gynecol Oncol (2016) 143(3):552–7. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.09.011

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

46. Gardner, GJ, Reidy-Lagunes, D, and Gehrig, PA. Neuroendocrine Tumors of the Gynecologic Tract: A Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) Clinical Document. Gynecol Oncol (2011) 122(1):190–8. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.04.011

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

48. Wang, R, Xiao, Y, Ma, L, Wu, Z, and Xia, H. Exploring a Better Adjuvant Treatment for Surgically Treated High-Grade Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Cervix. Gynecol Obstet Invest (2022) 87(6):398–405. doi:10.1159/000527661

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

49. Hoskins, PJ, Swenerton, KD, Pike, JA, Lim, P, Aquino-Parsons, C, Wong, F, et al. Small-Cell Carcinoma of the Cervix: Fourteen Years of Experience at a Single Institution Using a Combined-Modality Regimen of Involved-Field Irradiation and Platinum-Based Combination Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol (2003) 21(18):3495–501. doi:10.1200/jco.2003.01.501

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

50. Nishio, S, Kitagawa, R, Shibata, T, Yoshikawa, H, Konishi, I, Ushijima, K, et al. Prognostic Factors From a Randomized Phase III Trial of Paclitaxel and Carboplatin Versus Paclitaxel and Cisplatin in Metastatic or Recurrent Cervical Cancer: Japan Clinical Oncology Group (JCOG) Trial: JCOG0505-S1. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol (2016) 78(4):785–90. doi:10.1007/s00280-016-3133-4

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

51. Nakao, Y, Tamauchi, S, Yoshikawa, N, Suzuki, S, Kajiyama, H, and Kikkawa, F. Complete Response of Recurrent Small Cell Carcinoma of the Uterine Cervix to Paclitaxel, Carboplatin, and Bevacizumab Combination Therapy. Case Rep Oncol (2020) 13(1):373–8. doi:10.1159/000506446

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

52. Frumovitz, M, Munsell, MF, Burzawa, JK, Byers, L, Ramalingam, P, Brown, J, et al. Combination Therapy With Topotecan, Paclitaxel, and Bevacizumab Improves Progression-Free Survival in Recurrent Small Cell Neuroendocrine Carcinoma of the Cervix. Gynecol Oncol (2017) 144(1):46–50. doi:10.1016/j.ygyno.2016.10.040

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

53. Lai, ZY, Yeo, HY, Chen, YT, Chang, KM, Chen, TC, Chuang, YJ, et al. PI3K Inhibitor Enhances the Cytotoxic Response to Etoposide and Cisplatin in a Newly Established Neuroendocrine Cervical Carcinoma Cell Line. Oncotarget (2017) 8(28):45323–34. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.17335

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

54. Zhang, X, Lv, Z, and Lou, H. The Clinicopathological Features and Treatment Modalities Associated With Survival of Neuroendocrine Cervical Carcinoma in a Chinese Population. BMC Cancer (2019) 19(1):22. doi:10.1186/s12885-018-5147-2

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

55. Dong, M, Gu, X, Ma, T, Mi, Y, Shi, Y, and Fan, R. The Role of Radiotherapy in Neuroendocrine Cervical Cancer: SEER-Based Study. Sci Prog (2021) 104(2):003685042110093. doi:10.1177/00368504211009336

Comments (0)