People with multiple sclerosis (MS) consistently report distinct types of stressful events prior to the onset of disease (Mei-Tal et al., 1970). They believe there is a relationship between stress and their symptoms (Mohr and Bhattarai, 2018). Almost 150 years ago, psychiatrist and neurologist J. M. Charcot, who named and defined MS, was the first to note a relationship between stress and MS. He described MS onset as a consequence of grief, vexation, and adverse changes in social circumstances (Charcot, 1879). A clinician with 10 years of experience working with people with MS recognized some common patterns in how they perceive and respond to events, with particular types of stress events preceding disease onset and symptom worsening. These patterns, she found, are rooted in beliefs and social strategies formed in childhood that increase stress through the people’s lives.

The challenge in presenting this model is the empirical literature on stress and MS does not include the types of stress observed. This absence could explain why studies on the relationship between stress and MS yield inconsistent results (Jiang et al., 2022). They look for correlations using measures of stress that are at best only tangentially related to patient reports and clinical observations. This gap in the literature led to a thorough examination of how stress is measured, which then led to an even deeper inquiry into the evolution of stress models. Current models of stress and disease typically look at traumatic or major stressful events. They describe the behavioral and physiological effects of stress, but fail to explain the psychological process by which stress events lead to stress responses. They do not include the types of stressors and stress responses reported by people with MS.

In order to document and study the model of stress and MS formed through direct engagement with people with MS, the authors had to create a new model of stress and disease. The first half of this paper presents the resulting Developmental Model of Stress, exclusively using evidence in the available literature. This section shows the evolution of stress models and adds the psychological dimension that translates experiences into stress, briefly introducing how the Developmental Model of Stress could be applied to MS. Then it looks at the evolution of stress measurement in response to the models, using examples drawn from the MS literature to show the general principles. Finally, it details the relevant parts of developmental psychology that produce the lifelong patterns of maladaptive beliefs and behaviors that create stress, along with the early and ongoing physiological stress responses that contribute to disease development.

The second half of the paper applies the Developmental Model of Stress in its description of a new model of stress and MS. This model of stress and MS synthesizes converging evidence from clinical insights, patient reports, and medical and psychological literature into a coherent narrative. The original formulation of evidence-based medicine called for the balanced integration of empirical research and clinician insight (Sackett, 1997), while patient-centered medicine listens carefully to the person (Stewart et al., 2024). Combining science, clinical experience, and patient report is fundamental to Western medicine, as expressed by Osler (1892). This section provides an initial framework for identifying specific types of stress commonly found among people with MS. The description of this comprehensive model will include clinician and patient voices combined with the literature to support more complete understanding of how the model might appear from each of these three perspectives. The model could lead to earlier identification of people at risk for developing MS and a broader range of better-targeted therapies.

The developmental model of stress Evolution of stress modelsStress is often thought of in terms of the original Stressor-Stress Response Model put forth by Selye (1936). A threat to the organism’s integrity, the stressor, occurs and elicits an automatic stress response in the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. This fight or flight response to stress (Cannon, 1915; Cannon, 1929) is designed to marshal the body’s resources for managing the threat and returning to homeostasis. The stressor-stress response model is suited to managing discrete, short-term threats, after which the chemical response rapidly dissipates. With prolonged stress, the body enters Selye’s third stage, exhaustion, when the stress response itself creates problems in the body.

Lazarus’s Cognitive Model of Stress (Lazarus et al., 1952) introduced the role of appraisal. If the threat is appraised as larger, more imminent, or more dangerous, then the body activates a larger stress response. If the person is unconscious and unable to cognitively appraise the threat, no stress response occurs (Symington et al., 1955). The cognitive model expanded the previous stressor-stress response model to include (1) an internal or external stressful event, (2) conscious or unconscious evaluation of the event, (3) physical or mental coping processes, and (4) the stress reaction, a complex combination of physical and mental responses (Lazarus, 1993).

Engel’s Biopsychosocial Model of Medicine (Engel, 1977) added needed nuance to the cognitive model of stress, recognizing that all four steps of the cognitive model are responsive to physical, psychological, and social influences. The understanding of stress becomes richer by including the often-conflicting roles of emotions, meaning-making, biochemistry, social influences, beliefs, preferred coping mechanisms, and temperamental characteristics (Sapolsky, 2004; Surachman and Almeida, 2018). Each of these aspects influence each other, creating feedback patterns that can impact physical and mental stress responses (Oken et al., 2015). Importantly it introduced the role of psychological and social stressors. Stressors no longer required an outside event and could be self-created through sensitized thoughts and beliefs (Lazarus, 1999). Interpersonal stressors, especially those during the early developmental period of life, gained increasing attention (Pynoos et al., 1999), leading to the recognition of complex forms of response to stress. The freeze response (i.e., stress-induced immobility) was recognized as active in humans and not just other animals (Barlow, 2004). When stress researchers finally started including women in their studies, they identified another common but previously unrecognized form of stress response, “tend and befriend” (Taylor et al., 2000), referring to responding to stress by tending to and seeking connection with others. This response is most common among women and children, and most often occurs in response to interpersonal stressors. These added complexities made it difficult to develop a unifying model of stress and disease that encompasses everything from cellular dynamics to social influences.

Miller et al.’s Biological Embedding of Childhood Adversity Model (Miller et al., 2011) is one such comprehensive model. It describes the experiences of early childhood as laying the biological and behavioral foundations for future stress-related responses that are predictive of disease development. Among its key features is the life-long influence of beliefs and behaviors adopted during childhood on each of the cognitive model’s four steps.

This paper proposes a Developmental Model of Stress. It adds the findings of psychology in Engel’s biopsychosocial model (Engel, 1977) to Miller et al.’s Biological Embedding Model (Miller et al., 2011). Developmental psychology documents the dynamics of core belief formation during early childhood, and especially how the beliefs are influenced by the parent–child relationship. These core beliefs serve as the interpretive framework that guides the child’s perception of and response to environmental conditions. The Developmental Model of Stress begins with the adoption of maladaptive beliefs about self and others due to challenging interpersonal relationships during infancy and early childhood. These problematic beliefs create the conditions for distorted threat perception and limited coping responses through later childhood and into adulthood, leading to increasing levels of ongoing stress. The pattern of constant and growing stress, together with the biological changes in response to stress, creates the physical and psychological preconditions for the addition of a new stressor to overload the stress response systems and trigger the development of a physical disease. This is consistent with the diathesis-stress model of disease onset.

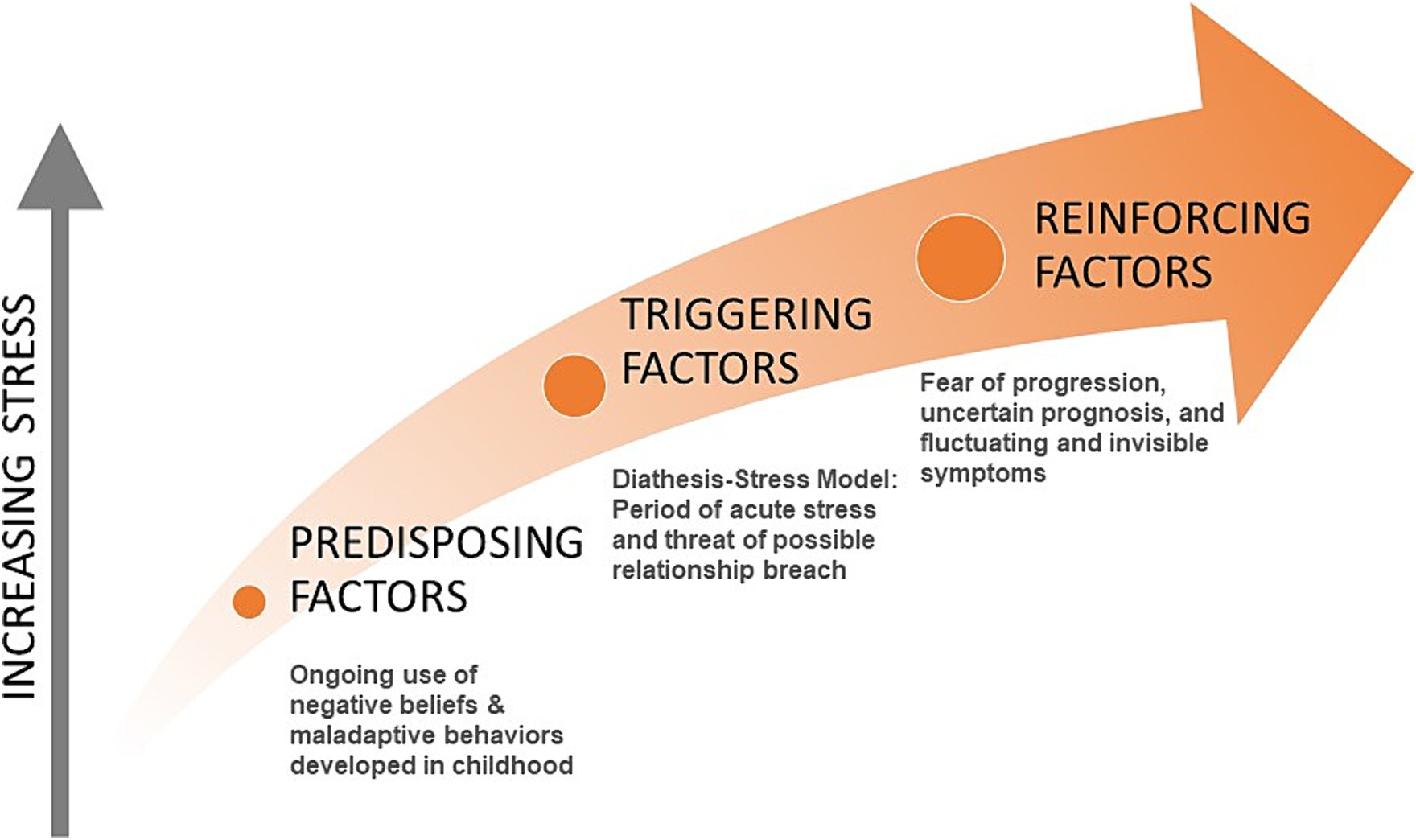

For people with MS, the cause of overload may take the form of a period of acute stress and a threat of a relationship breach for which the person’s beliefs and coping skills are insufficient, leaving them feeling trapped or stuck and eliciting the freeze response. This leads to the first physical symptoms of MS, such as paralysis, numbing, and optic neuritis, and the consequent diagnosis. The diagnosis, with its poor prognosis and subsequent worsening of symptoms, introduces a new set of stressors which they attempt to manage with the same set of maladaptive beliefs and behaviors, adding to the mental and physical stress loads and contributing to disease progression (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Categories of stress in people with MS.

Evolution of stress measurementAs shown by the evolution of stress models, stressful events do not equate with stress response. Rather it is the appraisal of and response to events, informed by the person’s core beliefs, that leads to the experience of stress and its mental and physical consequences. Yet much of the research on stress and disease still uses counts of events or types of events based on the idea of cumulative risk, which assumes that more events implies more effects (Evans et al., 2013; McLaughlin and Sheridan, 2016). Studies based on counts of events must be interpreted with caution due to the presence of so many mediating and moderating factors not considered in the measures.

Moving from the stressor-stress response model to the cognitive model of stress introduces multiple appraisal, cognitive, and emotional elements. A recent systematic review looking at stress and MS reported that the included studies had inconsistent conclusions, perhaps partially due to the lack of nuanced information about stress (Polick et al., 2022). Studies that measure self-reported stress severity, or “subjective cognitive perception” (Koolhaas et al., 2011), rather than only counts of events have consistently shown significant and possibly causal relationships between stress and MS onset and progression, while those using counts of events have yielded less consistent results (Briones-Buixassa et al., 2015; Polick et al., 2023a; Shields et al., 2023).

Adding only a single variable for stress intensity, which itself is the final of four steps in the cognitive model of stress, significantly improves predictive ability (Shields et al., 2023). The Life Events and Difficulties Schedule (Brown and Harris, 1978/2001) uses a semi-structured interview format allowing greater depth of inquiry, but still results only in counts of events and a single measure of stress intensity. It has been found to predict MS onset based on perceived stress severity in the year or two prior to diagnosis (Warren et al., 1982; Grant et al., 1989).

Although it would be impossible to capture all the complexity introduced by Engel’s biopsychosocial model (Engel, 1977), a more recently developed tool combines the depth afforded by interviews with the rigor and ease of self-report instruments. The Stress and Adversity Inventory (Slavich and Shields, 2018) measures relevant biopsychosocial dimensions, such as domains of social and economic factors, acute and chronic stressors, timing of stressors, and social-psychological characteristics. Each stressor selected by the respondent is followed up with questions regarding severity, frequency, timing, and duration. Initial testing shows strong predictive ability for a range of medical diseases and metabolic functions, and is particularly effective in predicting autoimmune diseases. It captures some of the effects of stress as well, such as mood disorders and positive and negative affect, but does not address the beliefs that give rise to these effects or the coping behaviors that ensue. The Life Events and Difficulties Schedule (Brown and Harris, 1978/2001) and the Stress and Adversity Inventory are the two approaches recommended as current best practices for measuring stress in health research (Crosswell and Lockwood, 2020).

The two measures recommended above, and especially the Stress and Adversity Inventory with its broader scope and greater detail, effectively measure some types of stressful events and the emotional response to those events. They do not, however, capture the psychological dimension of why the events were experienced as stressful, nor the seemingly smaller events that give rise to stress. Automatic thoughts and expectations, along with coping strategies provide a more complete understanding of what leads to the experience of stress. These arise from core beliefs developed in childhood, which are usually modified through life experience.

There are many self-report instruments to identify core beliefs, though they may not be measuring what they intend. Core beliefs are typically unconscious and not available for recall when responding to test questions (Beck, 2020). In contrast, automatic thoughts and expectations, which result from core beliefs, are available for recall (Beck, 2020). The scales used to measure core beliefs are typically validated against measures of the effects of the beliefs, such as depression, eating disorders, or relationship difficulties. A review of 25 scales measuring beliefs reported that none of the scales tested their construct validity against an assessment of core beliefs uncovered directly through therapeutic exploration (Bridges and Harnish, 2010). The results on these types of measures can also be strongly influenced by the test-taker’s mood at the time of the test (Stopa and Waters, 2005). With these limitations acknowledged, the Young Schema Questionnaire-Rasch version seems a good quality scale not targeted to a particular diagnosis, so is able to capture a broader range of specific beliefs (Yalcin et al., 2022, 2023). It, like other belief scales, is subject to response bias in that people who use an avoidant coping strategy tend to underreport negative beliefs (Young, 2003).

Most core beliefs, and especially negative core beliefs, are unconscious (McBride et al., 2007; Beck, 2020). Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has a variety of techniques for identifying beliefs, however they are most often used for identifying automatic thoughts or intermediate beliefs, and not the limiting, unconscious core beliefs developed in childhood. Some of these techniques are based on tools first developed in hypnotherapy (Watkins, 1971). Most therapists are not trained in these techniques, as CBT primarily focuses on present-day thoughts and feelings, leaving exploration of childhood experiences to psychoanalysts (James and Barton, 2004; Wedding and Corsini, 2018). Hypnosis provides faster and more effective access to core beliefs than does CBT (Brink, 2005; Dowd, 2005). Hypnotherapy and neurolinguistic programming techniques allow rapid access to the unconscious patterns of belief and behavior, making them the preferred method for identifying core beliefs (Dilts, 1990; Davis and Davis, 1991; Lucas, 2007).

Developmental psychology and stressStressful events such as adverse childhood experiences often lead to problems with physical and mental health in adulthood (Felitti et al., 1998; Berens et al., 2017; Polick et al., 2023b). Research on stress and disease has for the most part focused on stress events, especially traumatic events, and biological responses to stress. Many of the physiological pathways involved in translating the experience of stress into physical disease have been identified and mapped (McEwen, 1998; Miller et al., 2009; McEwen, 2015). The events have also been shown to be associated with maladaptive beliefs and behaviors (Miller et al., 2011), but the pathway for translating stress-related experiences into the types of problematic threat assessment and coping behaviors observed has not commonly been included in the discussion (Friedman, 2008).

Different types of early life adversity lead to different types of psychological and physiological responses. Preliminary evidence suggests these differences might usefully predict a variety of diseases (Berman et al., 2022). Studies using counts of adverse childhood experiences can still be informative when findings are broken down by types of stressors. Using counts of adverse childhood experiences, a large-scale cohort study (Riise et al., 2011) found no link between later diagnosis with MS and severe physical abuse or forced sexual activity during childhood and adolescence, while another count-based study found childhood experiences such as household dysfunction and neglect were linked to MS onset (Shaw et al., 2017). A third study looking at counts of childhood stressors found no overall statistically significant correlation with later MS development, but when broken down by type of stressor again showed emotional stressors were more correlated with MS onset than were physical stressors (Briones-Buixassa et al., 2017). A fourth study looking at the relationship between MS fatigue symptoms and types of childhood adversities found childhood emotional neglect and emotional abuse were the strongest predictors of fatigue (Pust et al., 2020).

A meta-analysis of different kinds of childhood adverse events and their association with negative core beliefs (Pilkington et al., 2021) found the strongest predictors of the child developing negative core beliefs were all emotional or interpersonal in nature. It also showed physical stressors influence the development of negative beliefs very little. Negative core beliefs lead to heightened threat perception and influence coping responses (Rakhshani and Furr, 2021). Children with negative core beliefs then report a higher number of adverse events through their later childhood and teen years (Rakhshani and Furr, 2021).

Developmental stressThe World Health Organization defines stress as “a state of worry or mental tension caused by a difficult situation” (WHO, 2023). Stress is first and foremost a psychological state. It results from the common, ordinary, everyday way we think of ourselves and the world. It is not dependent on outside events, minor or major, to create. One person may feel relaxed sitting in traffic while another may escalate more easily. The psychological state is what gives rise to the physical and psychological responses to stress. As the evolving models of stress show, individual agency links the stressor and the stress response. But what gives rise to the psychological experience of stress? Existing research points in an interesting direction.

Developmental psychology shows the nature of this agency during early childhood and how it later influences stress experiences. Erikson’s Psychosocial Development Theory describes the impact of social experiences from infancy onward through eight stages over the lifespan, with each stage presenting challenges and opportunities for growth (Erikson, 1950; Erikson, 1959; Erikson, 1968). Gilligan’s research with women suggested the need for an expansion of Erikson’s model (Gilligan, 1982). Franz and White integrated the two perspectives into an eight-stage model incorporating both Erickson’s emphasis on separation and individuation and Gilligan’s emphasis on care and relationship, finding both aspects are important for healthy development in both sexes (Franz and White, 1985). When these early developmental stages are not successfully completed, the child can form unhealthy beliefs about themselves and the world around them (Marcia and Josselson, 2013). Extensive empirical research supports these models (Vaillant and Milofsky, 1980; Bosma and Kunnen, 2001), though with some flexibility in the ages associated with each stage (Vaillant and Milofsky, 1980).

Each child is born with a distinct temperament, with some traits inherited and some unique to the individual (Saudino, 2005). Temperament is defined as the innate attitudes and behaviors a child has for experiencing and relating to the world around them (Friedman and Schustack, 2007). These traits are generally stable across the lifetime (Thomas and Chess, 1977), and include basic emotional needs and patterns of expression (Russell, 2003; Panksepp, 2005).

The child may change the expression of their temperament through learning and conditioning in response to caregivers. Goodness of fit refers to the degree of congruence between the personality and preferences of a parent with the temperament of the child (Chess and Thomas, 1991). A close-enough matching supports the child’s psychological and social development and creates a positive relationship with the parent, while poor matching may introduce developmental delays and adversely affect the nature and quality of the relationship with the parent (Newland and Crnic, 2017). Warm and attentive care from parents that is responsive to the child’s needs can foster the development of positive core beliefs about self and others, while inconsistent or ambivalent attention from parents can foster the development of negative core beliefs about self and others (Wellman and Gelman, 1992; Wearden et al., 2008).

The relational difficulties that form the roots of limiting beliefs and result in maladaptive behaviors need not be traumatic or abusive in nature. Infants are extremely social beings, reliant on their caregivers for emotional feedback and learning. For example, when a mother or father holds their baby but does not mirror back the baby’s facial expressions, the baby goes into a state of extreme distress (Tronick et al., 1978; Mesman et al., 2009). The overwhelm of the infant’s central nervous system can be so severe the child may physically collapse (Tronick et al., 1978; Mesman et al., 2009). Even when mirroring returns, the infant’s happiness response is somewhat reduced. This shows how even small mismatches can lead to formative changes in the child’s emotional development. There are many possible reasons a parent may not be able to be emotionally present to a child, but if it persists for more than short periods it can lead to impairment of the child’s emotional and social development (Bornstein, 2014).

Negative core beliefs, also referred to as maladaptive cognitive schemas or early maladaptive schemas (Young et al., 2003), create the child’s basic “rules for living.” These negative beliefs are directly associated with not successfully completing developmental stages due to the nature of the parent–child relationship (Thimm, 2010). They form the person’s identity and patterns of relationship with self, others, and the world. Normative development shows the core beliefs formed in early childhood through the parent–child relationship typically adjust and modify in response to later engagement with peers during adolescence. Negative core beliefs formed in early childhood are more persistent, remaining in place despite peer influence (McCarthy and Lumley, 2012). They remain fixed and outside the person’s awareness well into adulthood (Tang et al., 2020).

All input to the person’s awareness is filtered through these beliefs. Negative core beliefs lead to distorted perception of outside events that reinforce these negative beliefs. The person is more likely to recognize, interpret, or recall information that matches their negative beliefs and ignore or not even perceive information contrary to their beliefs (Ball, 2007; Beck, 2020). This unconscious reinforcement causes the maladaptive beliefs to become resistant to change later in life (Riso and McBride, 2007; Curran et al., 2021).

Psychological effects of developmental stressApplication of the Developmental Model of Stress includes the role of negative beliefs formed in early childhood leading to characteristic experiences of stress. These may vary with different diseases. A broad range of psychological factors contribute to MS onset and symptom severity that are distinct from people who do not have MS (Liu et al., 2009). This includes aspects of mood, emotions, threat expectations, coping responses, and social relationships (Liu et al., 2009). All of these can be related to negative core beliefs.

Early adversity may lead the child to develop maladaptive beliefs and behaviors that increase the frequency and types of stressor perception (McLaughlin et al., 2014). The dysfunctional patterns of threat assessment occur both consciously and unconsciously, continuing into adulthood (Finlay et al., 2022). The brain’s pathways for threat detection become increasingly over-sensitized through ongoing perception of threats, leading to even more detection of stress events (McEwen, 2017). This pattern of constant alertness combined with distorted brain function can lead to increased stress even at rest (Lanius et al., 2017).

The negative core beliefs developed in childhood have been found to correlate with later distortions in mood and neurocognitive development (Beck, 2008). A disengaged or overly-controlling parent can lead the child to develop negative beliefs about themselves (Garber and Flynn, 2001). These negative self-concepts may be adjusted during teen years if parents change their engagement style, but the negative self-beliefs tend to continue into adulthood (McArthur et al., 2019). Negative core beliefs also lead to problematic relationships with others, and these patterns too continue into adulthood (Waldinger et al., 2002; Simard et al., 2011). They often lead to a sense of constant and generalized anxiety (Koerner et al., 2015), which increases the experience of stress and continues into adulthood (Tariq et al., 2021). They predispose the person to have difficulty recognizing and managing their own emotions, especially when the beliefs were related to unmet needs for attachment and autonomy (Pilkington et al., 2024). Further, they produce lifelong maladaptive coping patterns (Curran et al., 2021).

This combination of interacting maladaptive beliefs and behaviors lead to complex and compounding challenges in self-identification and relationships with others. The initial small-scale parent–child difficulties during early childhood, when repeated over time, lead to developmental disruptions in the child’s self-and social awareness, emotional attachments, cognition, and emotional awareness (Cruz et al., 2022). These dysfunctional developmental patterns create a self-perpetuating cycle of ever-increasing emotional tension as the child tries to apply them in the larger world, leading to increasingly complex patterns of maladaptive beliefs and behaviors (Herman, 1992). These more complex patterns of stress perception and response share many features with post-traumatic stress disorder (Chiu et al., 2023). The more complex stress-based psychological difficulties may first show themselves in late teen years or early adulthood (Cloitre et al., 2009), yet are most often found among people who experienced interpersonal developmental challenges (Giourou et al., 2018). These patterns of complex responses have been found to mediate the relationship between childhood developmental challenges and disease development (Ho et al., 2021).

Physiological effects of developmental stressMost research on the physiological effects of stress look at adults. While this approach makes sense because most stress-related diseases are typically found in adults, the physiological precursors can be found in childhood just as for the psychological precursors. Poor quality parent–child interactions have been shown to increase childhood cortisol levels during the first 5 years of life (Moffett et al., 2007). A longitudinal study found it also predicted decreased brain volume in both later childhood and mid-to late-adolescence, particularly in the emotion and executive centers, to a similar degree as found in children who had experienced severe traumatic events (Tyborowska et al., 2018).

Contrary to early thinking that activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis occurred in response to threats to biological integrity, the adrenal response is almost exclusively triggered in response to psychological stressors and only barely responds to physical stress (Mason et al., 1976). No research has yet been done with humans to distinguish different types of physiological responses to different types of early life stressors. Animal models suggest environmental, physical, and early-life relational stressors all activate the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis to varying degrees, and increase its activation with repeated exposures, but only early-life relational stressors reduce the ability to down-regulate the stress response (Kuhlman et al., 2017).

The original article on Miller’s Biological Embedding model provides detailed reporting of the physical changes in childhood observed in response to stress (Miller et al., 2011). These include changes in the development and function of the endocrine and central nervous systems, all the way down to cellular metabolic functions. These changes program the body for heightened reactiveness to stress and reduced immune functions. The paper also proposed some pathways by which this dysregulation occurs that have since been supported (Enoch, 2011; Dye, 2018), showing changes even down to what parts of DNA get expressed (Bigio et al., 2023; Zhou and Ryan, 2023).

The above physiological stress responses in childhood create the early predispositions for greater physiological dysregulation later. Stress is causally associated with changes in chemical balance, metabolism, organ function, and tissue structure. When stress become perseverative, it causes ongoing and lasting physical changes (Berens et al., 2017). McEwen’s concept of allostatic load represents the body’s multi-system adaptation to chronic stress (McEwen and Stellar, 1993). Allostatic overload is when even this complex compensatory system can no longer manage demands, leading to the severe dysregulation of metabolic, cardiovascular, and immune functions, along with the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems, and changes in the structure and function of the brain (McEwen, 2017). This severe dysregulation of organismic systems sets the stage for an acute stressor to trigger the onset of a physical disease, following the diathesis-stress model of disease development (Lazarus, 1993; Monroe and Cummins, 2014).

The evidence for the role of stress in multiple sclerosis is clear. High allostatic load is common in people with MS (Waliszewska-Prosół et al., 2022). It has been shown to cause most of the symptoms of MS. It can cause prolonged inflammation (Gold et al., 2005; Lenart-Bugla et al., 2022), neurodegeneration (Harnett et al., 2020), and motor dysfunction (Snell et al., 2022); and increase disability (Gold et al., 2005). High stress and allostatic load can also lead to chronic pain and emotional dysregulation (Nakamoto and Tokuyama, 2023). Linking this stress-related allostatic load to psychological processes can help better inform the biological development and progression of MS.

This paper has so far introduced a model of stress and disease that moves beyond original formulations identifying adverse or traumatic events as the cause of stress, and adds the role of childhood development as a critical factor in understanding stress through adulthood. The maladaptive beliefs and behaviors originating from developmental challenges are robust, remaining essentially unchanged through life unless directly named and addressed. These unconscious beliefs and behaviors profoundly influence stress perception and response. The remaining sections of the paper will describe how these principles can be applied to the study of stress and MS.

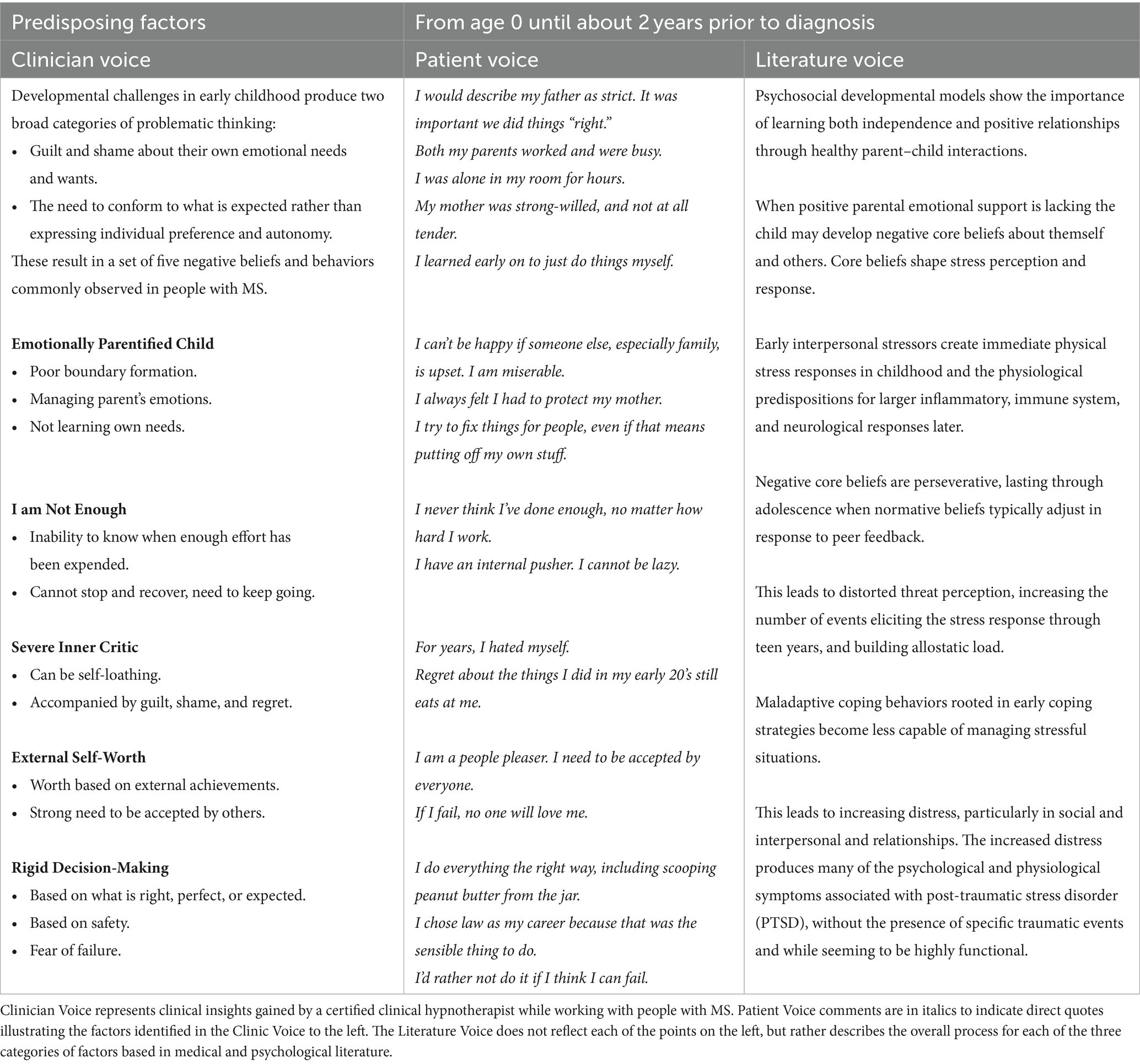

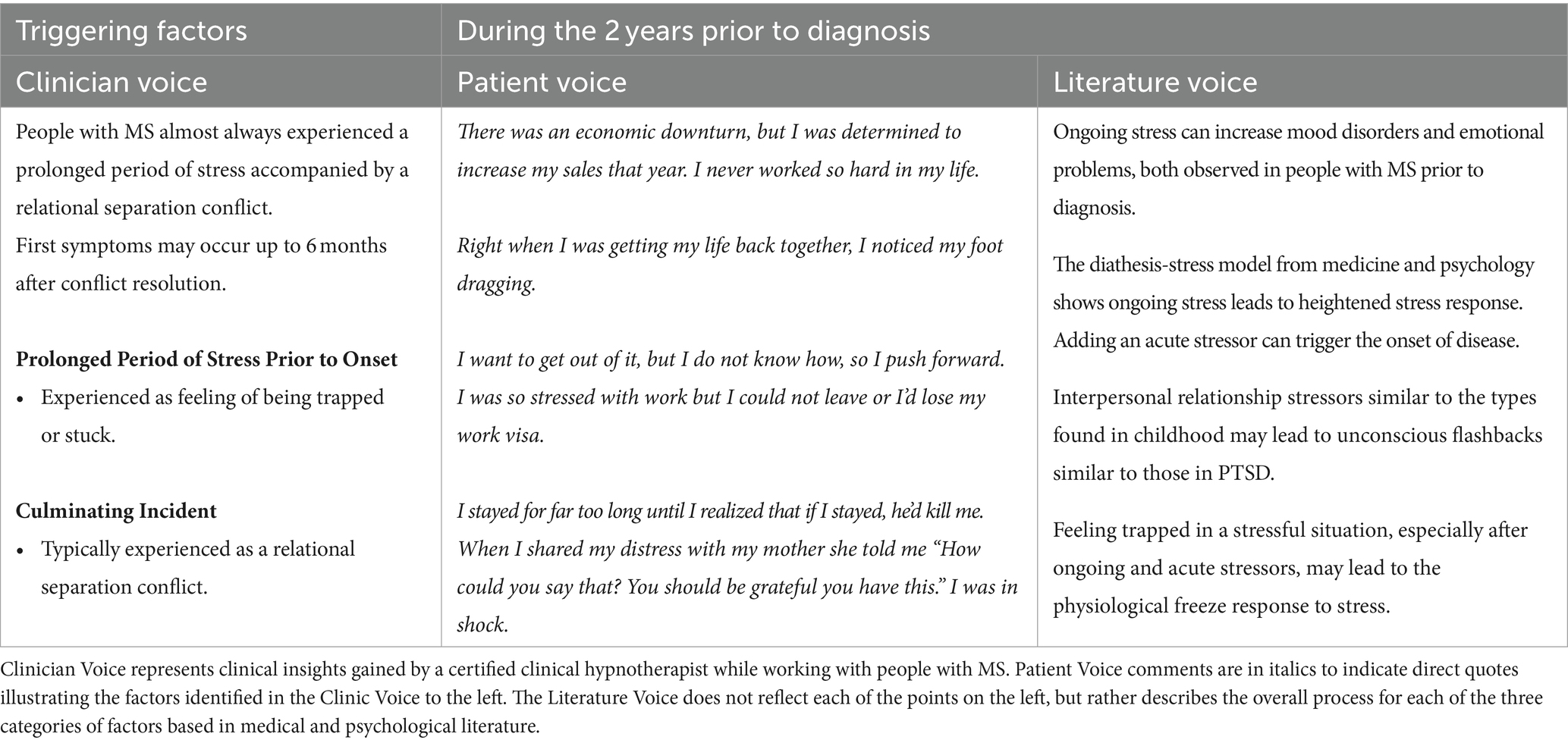

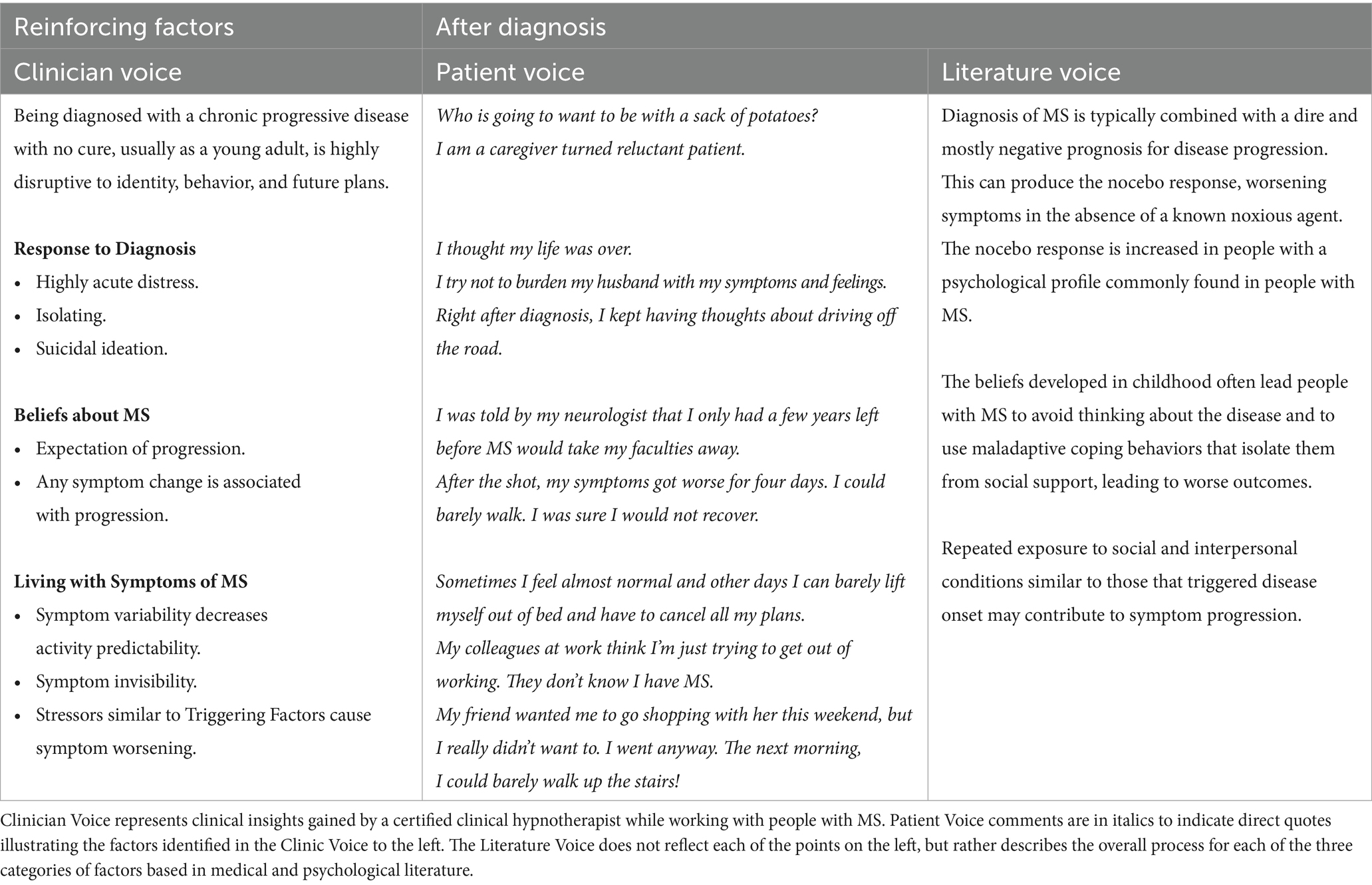

The developmental model of stress applied to MSThe Developmental Model of Stress proposed here provides a tool for further inquiry into the stress-MS relationship. The following model of stress and MS includes three categories of stress experienced by people with MS over their lifetime that contribute to the physical expression and progression of the disease. These categories include (1) predisposing factors developed in childhood, (2) triggering factors preceding disease onset, and (3) reinforcing factors that continue during the course of the disease. These factors were identified through clinical observation, patient reports, and concurrent examination of the literature. These three perspectives are illustrated in Tables 1–3. Clinician Voice represents clinical insights gained by a certified clinical hypnotherapist while working with people with MS. The Patient Voice comments are in italics to indicate direct quotes recorded during the hypnotherapy sessions illustrating the factors identified in the Clinician Voice to the left. The Literature Voice does not reflect each of the points on the left, but rather describes the overall process for each of the three categories of factors based in medical and psychological literature.

Table 1. Model summary – predisposing factors in three perspectives.

Table 2. Model summary – triggering factors in three perspectives.

Table 3. Model summary – reinforcing factors in three perspectives.

Consistent with how this model was developed, the rest of the paper will include all three sources of information. Most of the following discussions of the identified factors will begin with how they are identified and understood clinically, then be illustrated with direct quotes from clients in italics, and then be followed by a discussion of the relevant scientific literature. This pattern allows a richer understanding of the dynamics involved and could lead to more fruitful discussions between people with MS and the people providing care.

Predisposing factorsClinical observation found that people with multiple sclerosis appear to have a common set of negative core beliefs and maladaptive behaviors that are distinct from those of clients with other diseases and disorders. These beliefs and behaviors were experienced by clients as fixed and defining of self, others, and the world. “This is just who I am” and “Doesn’t everyone fear failure?” were common reactions at the start of exploring these beliefs.

Two childhood developmental challenges were detected that may have contributed to the formation of the majority of the commonly observed negative core beliefs. These were the failure to have core emotional needs met and not learning to assert independence. In particular, clinical observation found clients experienced (1) guilt and shame about their own needs and wants, even to the point of not being able to recognize them, “I don’t have needs” and (2) the need to conform to external wishes, such as doing things the “right way” or what seems to be expected, rather than expressing individual preferences and autonomy.

While the parent/child interactions that created these developmental challenges were not necessarily traumatic, they were impactful. Not getting their emotional needs met could have been caused by experiences such as being an only child with busy professional parents; the mother or child being hospitalized during early childhood; or having teenage parents, a distracted grieving parent, or a worried parent. “I was alone in my room for hours and hours.” Additionally, adaptation to external expectations rather than developing autonomy seemed to be influenced by a strict, controlling, or corrective parent, “My dad always said that I could do better,” or through the child managing the parent’s emotions, taking care of them to “keep my mother from worrying about me.”

As described in the Developmental Model of Stress, negative beliefs and maladaptive behaviors are primarily formed through parent–child relationship challenges. Most relevant to people with MS, these challenges include parental disengagement, where a child’s emotional needs are not met, or an over-controlling parent, where autonomy is not encouraged (Garber and Flynn, 2001; Thimm, 2010). Developmental challenges that include household dysfunction and neglect have been linked to MS onset (Shaw et al., 2017). The negative beliefs and behaviors adopted during childhood are key features in future stress-related responses predictive of disease development (Miller et al., 2011).

The distortions in self-identity, behaviors, relationships, and emotions introduced through developmental challenges are wide-ranging and overlapping, influencing each of the core beliefs and behaviors named in the Predisposing Factors section below. To give an example of the complexity involved, alexithymia is a contributing factor to several of the beliefs and behaviors identified as associated with MS. Alexithymia is usually defined as difficulty in identifying and processing emotions (Sifneos, 1973), but that definition has since been expanded. The difficulty in identifying emotions in self or others is particularly high for negative emotions (Luminet and Zamariola, 2018), and those with higher levels of alexithymia may actually display higher emotional responses to events and/or use emotional responses designed to take care of others (Luminet et al., 2021). It also includes an underdeveloped sense of self, lack of an internal world, and externally oriented thinking (Berenbaum and James, 1994; Lumley et al., 2007).

Alexithymia is found in about 10% of the general population (Honkalampi et al., 2001; Franz et al., 2008) and in up to 53% of people with MS (Chalah and Ayache, 2017; Eboni et al., 2018). It can appear in early childhood as a result of interpersonal challenges during developmental stages (Berenbaum and James, 1994; Wearden et al., 2003; Aust et al., 2013; Ditzer et al., 2023). Symptoms of alexithymia in childhood may slightly reduce during adolescence (Kekkonen et al., 2021), but when they arise in response to developmental challenges they typically remain stable into adulthood (Tolmunen et al., 2011; Ditzer et al., 2023). People with MS and alexithymia show higher rates of anxiety, depression, and fatigue (Chalah and Ayache, 2017; Eboni et al., 2018; Kekkonen et al., 2021), and continuous hyperactivity of the sympathetic nervous system’s stress response functions (Chalah and Ayache, 2017). Brain studies show that people with MS have difficulty in reducing emotional reactivity, especially in response to negative emotions, and that this inability is increased for those with alexithymia (Van Assche et al., 2021).

Alexithymia can also represent an attempt to “freeze” or deny emotions in an attempt to reduce emotional distress (Chahraoui et al., 2015). People with MS and alexithymia tend to use negative coping mechanisms, resorting to self-denial and submission strategies rather than more problem-focused strategies (Yilmaz et al., 2023). This is related to the tend-and-befriend stress response, used in the hope that tending to others’ need will reduce their own distress (Taylor et al., 2000). While higher levels of alexithymia is associated with higher emotional responses designed to take care of others (Luminet et al., 2021), this does not necessarily improve relationship quality as adults with alexithymia show significant difficulties in interpersonal relationships (Koppelberg et al., 2023) that can also affect physical health (Wearden et al., 2003).

The negative beliefs resulting from developmental challenges commonly found in people with MS were grouped into five main types. Each will include examples from clinical observations illustrated with direct quotes from people with MS. Rather than include all of the multiple facets of issues related to each factor, the literature following the clinical and patient voices will highlight one expression of the problematic belief or behavior.

Emotionally parentified childMost people observed had issues with personal boundaries and showed traits typical of people who in childhood were tasked with emotional caretaking of an adult. Blurring the lines of personal boundaries and roles was often subtle – taking on the role of emotional confidante to a parent, being a single parent’s companion, mediating family conflicts, or being emotionally supportive of a grieving or mentally ill parent. “I always felt I had to protect my mother.” This translated into a need to help significant others while not receiving such help themselves. “I cannot ask for help, no matter how much I need it” and feeling responsible for other’s emotional states “I can’t be happy if you are not happy.”

Emotional parentification means a role reversal in which the child takes responsibility for the emotional needs of a parent, rather than the parent providing for the child’s needs for attention, comfort, and guidance (Chase, 1999). This role reversal is recognized as destructive for the child and for the adult they will become (Boszormenyi-Nagy, 1973; Chase, 1999). This role reversal also contributes to building strong social skills as they learned to be attentive to others’ needs (Roling et al., 2020). In adulthood, this dynamic may show as assuming too much responsibility in relationships and hyper-attentiveness to taking care of others (Valleau et al., 1995). The need to be emotionally available for the parent when a parent is not as emotionally available for the child can lead to chronic anxiety and distress (Hooper et al., 2008; Engelhardt, 2012). While childhood parentification has not been studied in people with MS, one study found childhood experiences such as household dysfunction and neglect, which often leads to parentification, was linked to MS onset (Shaw et al., 2017). Childhood emotional parentification can be a driver for each of the other predisposing factors.

I am not enoughThe second common trait was the inability to know when enough effort had been expended. Clinical observation found that clients were constantly “doing 110%” effort in projects, continuing to think about projects after delivery, “Did I do enough?,” and were not easily able to prioritize what needs effort and what could be done less thoroughly. This also translated into an inability to stop and recover. “I keep thinking that I can stop when everything gets done, but there is always more to do, isn’t there?”

Parentification in childhood, when one is ill-prepared for the responsibilities, can lead to imposter syndrome in adulthood, with the person feeling like they are never good enough (Chase, 1999; Castro et al., 2004). The adoption of a parenting role as a child can also lead to becoming a chronic doer in adulthood, constantly seeking self-worth through being of service to others (Chase, 1999). The additional work performed leads to increased emotional distress rather than to increased satisfaction (Menghini et al., 2023). Childhood emotional neglect and emotional abuse, which leads to parentification and feeling not good enough, predicted MS fatigue symptoms (Pust et al., 2020).

Severe inner criticAnother trait consistently found in people with MS was a severe inner critic that analyzes and criticizes what one “should” be doing at all times. This was experienced as constant vigilance regarding one’s actions, often accompanied by guilt and shame. Consequently, many clients still held onto regret regarding actions taken in early adulthood “I should have known better.” In some cases, the result was self-loathing. “For years, I hated myself.”

Parentification in childhood means the child puts aside and never develops their innate talents and gifts, focusing instead on meeting the parents’ needs or expectations (Hooper et al., 2014). This pattern in childhood predicts proneness to feeling guilt and shame in adulthood (Wells and Jones, 2000). While guilt is associated with a behavior, shame is associated with a negative evaluation of self (Muris and Meesters, 2014). Proneness to self-conscious emotions, such as shame, guilt, and regret, increases in association with the types of childhood developmental challenges that produce parentification (Muris and Meesters, 2014). This constant self-criticism has been shown to contribute to depression and anxiety (Zhang et al., 2019), both common in MS, and to an insecure attachment style in relationships during childhood (Kim et al., 2020) and continuing into adulthood (Rogier et al., 2023). Self-blame has been shown to decrease the quality of life in people with MS (Kołtuniuk et al., 2021). The severe inner critic leads the person to satisfy their need for approval by turning outward, toward gaining approval from others (Muris and Meesters, 2014).

External self-worthClinical observation found that self-worth was most often based on external achievements, such as the desire for yearly promotions, as well as a strong need to be accepted by others. Worth and identity seemed to be defined by one’s actions. This would cause a severe fear of failure and assumptions such as “If I make a mistake, I am a failure” and “If I fail, no one will love me.”

While a healthy sense of self-worth begins in childhood through affirmation by a parent, a healthy sense of worth in adulthood needs to be internally based rather than based on external feedback (Reitz, 2022). Continued basing of self-worth on external feedback is often linked with insecure attachment or the experience of conditional love (Park et al., 2004). Being raised by conditional, negatively-evaluating parents, as well as experiencing parentification, can lead to the interpretation of one’s worth as a person through achievement and success alone, resulting in overwhelm, pressure to consistently perform optimally and prove one’s worth, and exhaustion (Muris and Meesters, 2014). The need to prove worth through achievement is especially prevalent in girls (Herrmann et al., 2019) and women (Menghini et al., 2023), which might help explain the increased incidence of MS in women since they started entering the workforce in large numbers (Dunn et al., 2015). Taking on too much work as a means to show worth can lead to increased perceived stress and decreased quality of life (Lichtenstein et al., 2019).

Rigid decision-makingLastly, a trait also common in people with MS was the criteria for decision-making. This style of decision-making is based on what is perceived as right, perfect, or expected, possibly developed in response to not feeling safe enough, feeling the need to please, or fearing rejection by a parent. “I try to do everything the right way.” One common request by clients with MS at the start of clinical sessions was, “Tell me what I need to do and I will do it.” This need to do it right or perfect, following external standards, also translated into the preference not to take action if there is a chance of failing. Though this common trait can affect small decisions, such as eating the “right” things, it can also negatively affect long-term decisions, such as career choice. “I chose law because it was a sensible career.”

As children develop, they learn to progressively transition from externally driven guidance and decision-making, to exhibiting more self-direction and autonomy (Frick and Chevalier, 2023). People with MS, however, continue to exhibit low self-directedness (Gazioglu et al., 2014). Adolescents who were parentified as children experience extreme distress when confronted with a possible breach in a relationship caused by the tension between who they experience themselves to be and what the other person wants them to be (Goldner et al., 2022). This often leads to them feeling stuck and defaulting to the other person’s needs (Goldner et al., 2022). Decision-making is already fraught with error for people with MS (Farez et al., 2014), especially when associated with ambiguous conditions or with risk (Farez et al., 2014). Alexithymia, common in MS as mentioned earlier, can cause inaccurate assessment of situations and make it difficult to make decisions or increase the likelihood of making incorrect decisions (Zhang et al., 2017). Parentification in childhood can influence the person’s choice of career, and make them more dependent on emotion-focused coping strategies (Boumans and Dorant, 2018; Roling et al., 2020). Decision-making based on perfection and elevated standards is a strong predictor of anxiety (Koerner et al., 2015), and perfectionism can cause maladaptive behaviors that contribute to MS fatigue (Magnusson et al., 1996).

Comparing beliefs between chronic diseasesMany studies have found correlations between specific core beliefs and the development of particular physical and mental health problems. For instance, types of core beliefs predict differences between mentally healthy and at-risk youth, and further analysis found unique negative core beliefs differentiate among types of mental illness (Cowan et al., 2019). Waller et al. found that distinct types of negative core beliefs predicted different types of eating disorders (Waller et al., 2003). Further, different types of skin disorders are associated with overlapping but distinct groups of negative core beliefs (Mizara et al., 2012). Identification of core beliefs associated with specific diseases might fruitfully be applied to the study of multiple sclerosis as well.

Table 4 represents a brief comparison of the limiting beliefs and behaviors observed in a convenience sample of clients with MS and clients with other chronic diseases in a single medical hypnotherapy practice. Data on beliefs and behaviors were documented from sessions with more than 60 people diagnosed with MS and 90 people diagnosed with other chronic diseases as part of the clinician’s detailed client notes. Beliefs were identified using the more direct approach of hypnosis and neurolinguistic programming. As this was not a formal study, there was no codified format for recording the information, but rather the clinical hypnotherapist’s client notes were kept according to best clinical practices, recorded with the aim of helping the clinician help the client. Thus, they were as accurate as possible, based on the clinical hypnotherapist’s integrity. This retrospective analysis of existing records was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the California Institute for Human Sciences. The clinician alone was authorized access to these records and was solely responsible for their interpretation. The five categories in the left column of Table 4 represent those beliefs found most commonly and most strongly among people with MS. Client records for people with other chronic diseases were then reviewed for the presence and strengths of these same beliefs. The table presents belief intensity for the most recent 10 clients in each disease category who completed sufficient sessions to gather a full representation of their underlying beliefs. Belief intensity was scored on a 4-point Likert scale.

Comments (0)