With the innovative advancements in science and technology over time, the average life expectancy is increasing. The incidence of cancer has been found to increase with the increase in life expectancy.[1] Cancer is the second most common cause of mortality after cardiovascular diseases.[2] Although symptoms vary site-wise, pain, fatigue, and weight loss represent the most common associated signs/symptoms in cancer patients. Insufficient pain control in cancer patients remains a significant challenge.[3-5] A meta-analysis published in 2007 highlighted that there has been no improvement in the treatment of cancer pain worldwide for over 40 years. It reported a prevalence of cancer pain of 59% in patients on anti-cancer patients, 64% in those with a terminal illness, and 53% across all stages.[6] Cancer-related pain has an overall prevalence of 45.6%, but this rate increases with the advanced disease stage (73.9%) and with the use of anti-cancer treatment (59%).[7]

Further, with the increase in patient load at hospitals, the home environment as the primary setting of care is now being preferred in patients requiring palliative care. Family caregivers (FCGs) are the prime caretakers of their patients and, thus, have an important role in managing cancer patients at home. According to the available literature, FCGs who care for patients in pain report higher rates of depression, anxiety, dread, weariness, appetite loss, and sleep disturbances than their peer group of FCGs who care for patients who are not in pain.[8,9] Thus, FCGs’ quality of life (QOL) might get hampered while taking care of their patients at home. As appropriate pain assessment by FCGs is important for taking care of patients’ pain at home, it thus becomes paramount to assess FCGs’ knowledge regarding cancer patients’ pain while simultaneously managing their QOL. With this backdrop, we structured a prospective study evaluating the various relationships between these various parameters.

Objectives Primary objectiveOur primary objective was to assess and evaluate FCGs’ knowledge and perception of cancer pain and to compare it with patients’ pain assessment.

Secondary objectiveThe secondary objective was to assess the impact on QOL of FCGs’, if any, while managing their patients at home.

MATERIALS AND METHODSConsecutive patients who met the study’s inclusion and exclusion criteria were included after receiving Institutional Ethics approval. Every patient was asked to name their primary FCG, which was the one who handled the majority of their care while they were at home. The patients who had histologically proven cancer, suffering from cancer-related pain and those registered under palliative care were included in this study. Informed consent was obtained from patients and FCGs’ before inclusion. The only point of exclusion was patients’ whose FCGs’ did not live with them. The study is registered under CTRI via registration number CTRI/2019/07/019973.

ProcedureAll the patients and FCGs’ completed a self-administered paper-based questionnaire during their hospital visit. FCGs’ own QOL was assessed using the caregiver quality of life index-cancer (CQOLC) questionnaire. Then, a member of the study team checked the completed questionnaires. Only completed questionnaires were included in the analysis. If patients or FCGs’ were illiterate, questionnaires were completed after a one-to-one interview with the investigators. The 16-item ordinal patient pain questionnaire (PPQ) and family pain questionnaire (FPQ) are used to measure participants’ awareness and experiences with cancer-related pain.[10] Nine items on the knowledge scale and seven on the experience scale make up each questionnaire. It was done using the Likert 11 score (0–10 points). The average score combined with the individual item scores was the overall subscale score (0–10). Every item has been structured with 0 denoting the most favourable result and 10 denoting the least favourable result. The total of the individual components was used to score each parameter.

The CQOLC scale, created by Weitzner et al., is a 35-item survey that asks questions on the physical, emotional, social, financial, and spiritual well-being of carers over the past seven days. It was used to gauge the effect of caring on the carer.[11] This measure was selected because it evaluated both the good and negative elements of providing treatment, had been validated in both inpatient and outpatient oncology settings, and had excellent test-retest reliability (0.95) and internal consistency (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

The CQOLC questionnaire has four conceptual domains: ‘Physical functioning, emotional functioning, family functioning, and social functioning.’ The 35 items on the CQOLC have a five-point Likert format, with the options being 0 (not at all), 1 (a little bit), 2 (somewhat), 3 (quite a bit) and 4 (very much). Ten of the items deal with the burden, seven with disruptiveness, seven with positive adaptation, three with financial concerns, and eight with single items that deal with additional factors (sleep disruption, satisfaction with sexual functioning, day-to-day focus, mental strain, informed about illness, patient protection, patient’s pain management and interest of family in providing care). The overall score for the instrument is obtained by summing the scores on each item on the CQOLC scale, and scores can vary from 0 to 140. A higher score indicates a better QOL for all items and domains used to assess QOL.

Statistical analysisA sample size of 93 was ascertained, assuming 60% had no/ negligible knowledge of pain management with 80% power and 5% level of significance with 10% precision taken for the study. For the patient and FCG demographic characteristics, descriptive statistics were calculated. For the total and domain scores of the FPQ and PPQ, the mean, standard deviation, and lowest and maximum values were computed. To decide whether to utilise a parametric or non-parametric test, the normality test using the Shapiro–Wilk method was utilised. The Chi-square test was used to determine whether there was a significant difference in the pain ratings of patients and FCGs for nominal variables. For all numerical variables, the t-test was utilised for parametric data and the Mann–Whiney U-test for non-parametric data. The relationships between patients’ ages, FCGs’ pain scores, and their own QOL scores were investigated using Spearman’s correlation coefficients. To analyse the data, IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences for Windows v23 was utilised. A significance level of P < 0.05 was used for all analyses.

RESULTSA total of 93 patients and their FCGs’ were recruited in this study. The baseline sociodemographics for both patients and their FCGs’ were obtained and are as depicted [Table 1]. The mean age of patients was 51.38 ± 5.701 years, and that of FCGs’ was 44.38 ± 6.396 years. The majority of FCGs (88.2%) were in the 51–65 years age group. The age distribution between the patients and FCGs was not significantly different (P = 0.416). There is, however, a significant difference in sex distribution between the patients and FCGs cohort (P < 0.001), predominantly female patients and male FCGs’ in this study. The majority of the patients (51.61%) and FCGs (67.74%) had less than a high school of education. Furthermore, the majority of the patients (74.19%) have poor performance status.

Table 1: Patients' and caregivers' baseline characterstics.

Characteristics Total number (%) Patients (n=93) Gender Male 33 (33.5) Female 60 (64.5) Age (mean±SD) 44.38±6.396 Education level <High school 48 (51.61) High school 09 (9.67) >High school 36 (38.70) Employment status Employed 51 (54.88) Self-employed 42 (45.16) Retired 09 (9.67) ECOG performance status 0–2 24 (25.80) 3–4 69 (74.19) Duration of illness <6 months 38 (40.86) >6 months 55 (59.13) Economic status High 07 (7.52) Middle 48 (51.61) Low 38 (40.86) Caregivers (n=93) Gender Male 71 (76.3) Female 22 (23.7) Age (mean±SD) 51.38±5.701 Education level <High school 63 (67.74) High school 05 (5.37) >High school 25 (26.88) Employment status Employed 81 (87.09) Self-employed 10 (10.75) Retired 2 (2.15) Economic status High 07 (7.52) Middle 48 (51.61) Low 38 (40.86)Amongst the patients and their FCGs, in the pain questionnaire, the mean scores were 35.91 ± 8.98 and 35.31 ± 10.15, respectively, in the knowledge domain while, in the experience domain, the scores were 27.19 ± 8.73 and 26.86 ± 6.11, respectively. The mean overall pain scores were calculated to be 63.11 and 62.17, respectively [Table 2a and b]. There was no significant difference between the pain assessment scores of FCGs and patients overall [Table 3].

Table 2a: Patient pain questionnaire.

Variables Total items Range Median Mean±SD Knowledge 9 14–58 37 35.91±8.98 Experience 7 4–55 28 27.19±8.73 Total 16 18–95 65 63.11±14.27Table 2b: Family pain questionnaire.

Variables Total items Range Median Mean±SD Knowledge 9 7–60 36 35.31±10.15 Experience 7 13–45 27 26.86±6.11 Total 16 32–105 62 62.17±13.03Table 3: Comparison of mean pain scores between patients and caregivers using t-test.

Pain questionnaire P-value Knowledge 0.669 Experience 0.763 Total 0.641For this study, the mean score of CQOLC was 79.09 ± 9.67. The COQOL index subscale scores of FCGs were 23.26 ± 3.41 for burden, 14.37 ± 2.89 for disruptiveness, 16.49 ± 2.85 for positive adaptation, and 6.32 ± 2.220 for financial difficulties [Table 4].

Table 4: CQOLC scores.

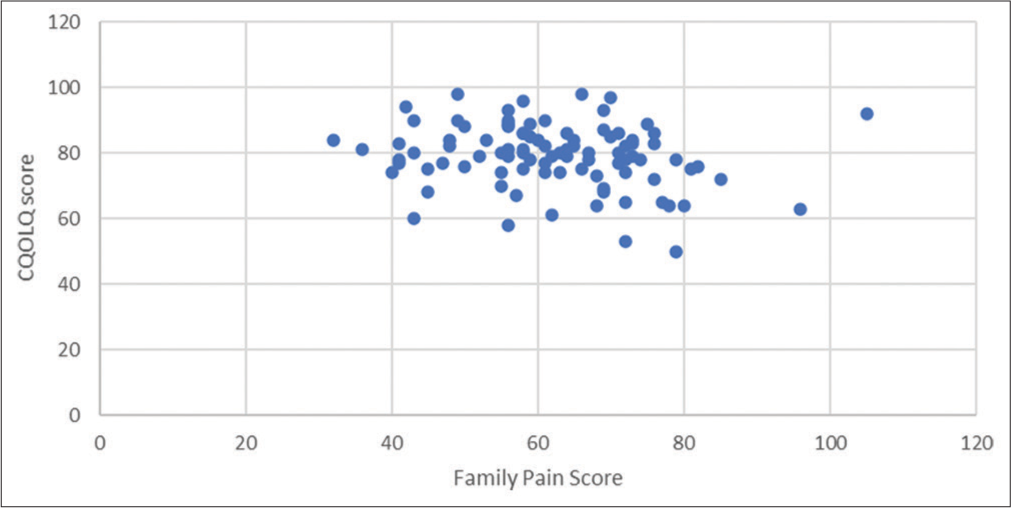

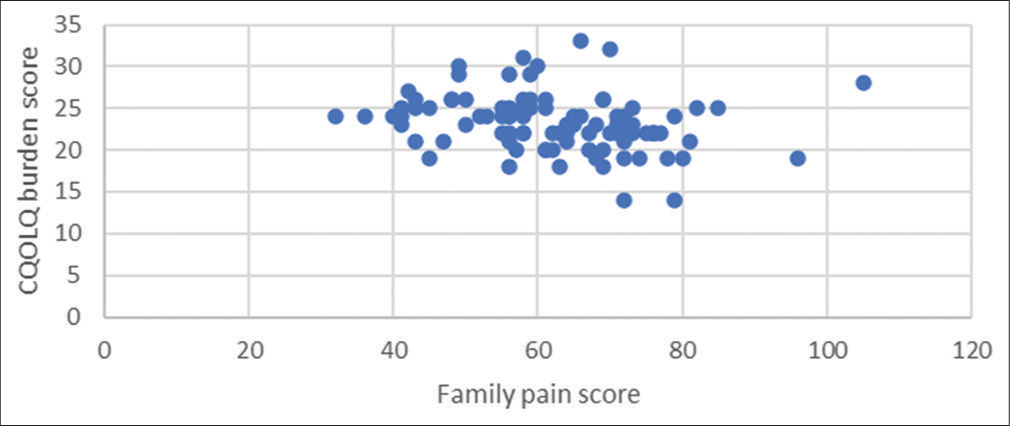

Variables Total items Range Median Mean±SD Burden 10 14–33 23 23.26±3.41 Disruptiveness 7 6–21 14 14.37±2.89 Positive adaptation 7 9–23 17 16.49±2.85 Financial difficulties 3 0–11 6 6.32±2.22 Total CQOLC 35 50–98 80 79.09±9.67No linear relation was elicited between the pain scores and the QOL scores, as depicted in the scatter diagram [Figures 1 and 2]. An inverse relationship was elicited between the total QOL and the pain assessment scores of FCGs, as well as the age of the patient. The difference was, however, majorly statistically non-significant (P > 0.5). Further, statistical significance was found only between the burden component of the CQOLC and the age of the patients (P = 0.034), as well as total pain knowledge (P = 0.007) and total pain scores (P = 0.001) of the FCGs [Table 5].

Export to PPT

Export to PPT

Table 5: Spearman's coefficient comparing QOL components (total and burden) with patients' and caregivers' age, knowledge, and experience parameters.

Correlation coefficient P-value QOL final vs. total pain scores of caregivers' −0.201 0.053 QOL final vs. total pain knowledge of caregivers' −0.184 0.077 QOL final vs. total pain experience of caregivers' −0.12 0.25 QOL final vs. age of caregivers' 0.031 0.766 QOL final vs. age of patients' −0.033 0.752 QOL burden vs. age of patients' −0.22 0.034 QOL burden vs. age of caregivers' 0.023 0.828 QOL burden vs. total pain scores of caregivers' −0.327 0.001 QOL burden vs. total pain knowledge of caregivers' −0.278 0.007 QOL burden vs. total pain experience of caregivers' −0.186 0.075 DISCUSSIONControlling cancer pain is a complicated process that involves the patient, the family, and the healthcare service providers. In this prospective analysis of 93 patients and their FCGs, statistical significance was found only between the burden component of the CQOLC and the age of the patients (P = 0.034), as well as total pain knowledge (P = 0.007) and total pain scores (P = 0.001) of the FCGs. However, there was no significant difference in the perception of pain between the FCGs’ and the patients. Similar findings were observed in a study done by Yesilbalkan et al.[12] In addition, there was no correlation between the QOL of FCGs and pain scores.

Cancer-related pain can be the cause of unwelcome circumstances in the patients’ functions. An increase in weariness and worry, a decrease in sleep and concentration, and other undesirable situations that impair a patient’s QOL can all be attributed to pain connected to cancer. Cancer pain may impair every part of life, including working, interacting with others, and managing sickness, if the treatment is not received.[13,14] The majority of the literature that is currently available shows that inadequate physician support for managing cancer pain, limited access to accurate information, and inadequate task preparation are the main causes of a suboptimal understanding of the main elements of pain management.[15] It has been noted that caregivers receive brief and disjointed explanations regarding cancer pain and its management from physicians and/or family and friends, with almost nil support for the evolving concerns and information regarding the nature of pain, its management strategies, proper management of side effects of medication used and their expected outcomes. Hence, their FCGs are left with no choice but to use their own experiences, and this may result in poor decision-making, feelings of helplessness, and a lack of confidence in times of need. Lee et al. found that concepts of dependence and tolerance were the primary lacunae in understanding the concept of pain management.[16] Furthermore, each of them had strong personal beliefs about the meaning of the intensity of cancer pain and the idea of disease progression in cancer. Optimal knowledge and appropriate skills enhance the skills of coping with the caregiving role, and inadequate knowledge regarding pain is a barrier to adequate pain control. However, in our department, with the help of palliative care physicians and healthcare workers, all the FCGs were counselled from the very 1st day, and this had a great impact on pain management. Hence, no significant difference was observed in the pain perception score of the patients as well as their FCGs. In a recent study, the researchers studied the impact of knowledge about pain in caregivers as a key factor in determining the level of pain experienced. A positive effect, that is, improvement in pain experienced, was noted in the group of the study population who gained significant knowledge following the intervention. On the contrary, decreased knowledge with no improvement in pain experienced was observed in the control arm.[17]

In a study by Berry and Ward, it was observed that care providers in hospice settings had several misconceptions and visible concerns regarding reporting pain and using analgesics appropriately, particularly about their side effects, addiction, role in the progression of the disease, and injection phobia.[18] People who were older and less educated expressed great anxiety that reporting pain may cause a doctor to become sidetracked from their primary objective of treating or curing cancer. The results of this study are encouraging because they demonstrate that FCGs with sufficient training in pain management have fewer obstacles to preventing cancer patients from receiving grossly inadequate pain therapy.

In a cross-sectional observational study by Vallerand et al.,[19], the association between the level of pain and the beliefs of the patient regarding pain was studied. In around 300 patients suffering from cancer, they recognised two indices defining the beliefs of cancer patients about pain: Proper knowledge regarding pain and identifying barriers to pain control. The authors found that there was a positive correlation between the level of patients’ pain and their distress level. Furthermore, it was studied that there is an evident relationship between the level of pain and their functional status and also a direct effect between the patient’s beliefs about pain and their level of distress regarding pain. Therefore, controlling the factors affecting pain level might alleviate the QOL.

Care delivered by FCGs is an essential part of high-quality care overall. It is well recognised that cancer significantly lowers the QOL not only for patients but also for carers. Some studies indicate that the impact on carers’ QOL in Asia is greater than in Western nations. QOL highlights symptom relief and, hence, may be used to assess the adequacy of pain management in cancer patients. Studies in China, Taiwan, Korea, Brazil, and Tokyo provide good evidence of the detrimental effect of pain on sleep, appetite, daily activity, mood, financial and emotional status, as well as the overall QOL.[20-22] This evidence has been supported by our study too. Cancer pain can be affected by pain intensity, clinical status, and treatment. It was seen that those with the end-stage disease had more pain and poorer QOL.[23]

Some of the limitations of the study included its small sample size and single-centre analysis.

CONCLUSIONAs per our analysis, FCGs had less knowledge and experience of patients’ pain, though statistically not significant. The critical role of FCGs in the management of cancer pain makes it very apparent that they need to be supported and educated if they are to potentially contribute to the process of achieving adequate control of pain. Further studies with larger sample sizes might help in strengthening the findings.

Comments (0)